I haven’t been this excited about a new translation in a very long time.

Currently, there are about 50 different English translations available, ranging from an interlinear Bible to free verse paraphrases. Wherever the Bible has gone, there are usually different versions of it. Even in the Dead Sea Scrolls, we find Hebrew manuscripts as well as Greek translations and paraphrases. So, in a day when we have so many English translations, is the Legacy Standard Bible (LSB) necessary? My answer to this question is yes.

A Brief History

But first, a very brief history of English translations. While I am not a fan of translations for translations sake, I recognize the need for accurate translations that people will read and treasure. As the King James translators wrote in their preface,

“Now to the latter we answer; that we do not deny, nay we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English, set forth by men of our profession, (for we have seen none of theirs of the whole Bible as yet) containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God.”

Which is just a cool way of saying that any English version is better than no English version. We are extremely fortunate to live in a day and age when the Bible is available so readily in a variety of formats and in a wide range of readable translations. So why the LSB?

To begin with, the LSB isn’t really a totally new translation. It’s a revision of the very popular New American Standard Bible (NASB) but with a few unique features that set it apart, which I will discuss below. The NASB first appeared as a New Testament in the 1960s, followed by the whole Bible in 1971. As the name implies, the NASB was a revision of the American Standard Version of 1901, which was an American version of the Revised Version of 1881 (New Testament) and 1885 (whole Bible) in England. The Revised Version was also, as the name suggests, a revision of an earlier English translation, the Authorized Version, more commonly known as the King James Version of 1611 (which, yes, was a revision of earlier versions, most notably William Tyndale’s New Testament – the first printed English translation from Greek).

Over time, languages evolve and new discoveries have led to updated versions of the Bible. With thousands of Greek manuscripts available, it’s remarkable that the textual differences, apart from spelling, are minimal and do not impact important teachings. This shows God’s preservation of His word.

That said, let’s go back to the 1970’s. I was that nerdy kid who carried his Bible to public school. My parents had purchased for me a Thompson Chain Reference Bible that was leather covered and I loved it. But I didn’t want to carry it to school for fear it would get damaged, so I asked my pastor what he suggested. Back then the number of translations (and the means to get them) was limited. There was the Living Bible, the Revised Standard Version, the Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible, the Amplified Version and a few others. While the American Standard was available, it was not readily available. My pastor suggested the NASB which I got in the New Testament (paperback) and read. That was followed by a rather bulky padded red covered version of the NASB, which is what I carried with me to school and church.

Uniqueness of the LSB

As mentioned, the LSB is a revision of the NASB95. There are four things I noticed right away when I first started reading the LSB:

- It keeps the tradition and beauty of its forerunners.

- It uses the name of God as found in the Hebrew Bible.

- It is consistent in use of Hebrew and Greek words when translating them into English.

- It’s readable while being accurately literal.

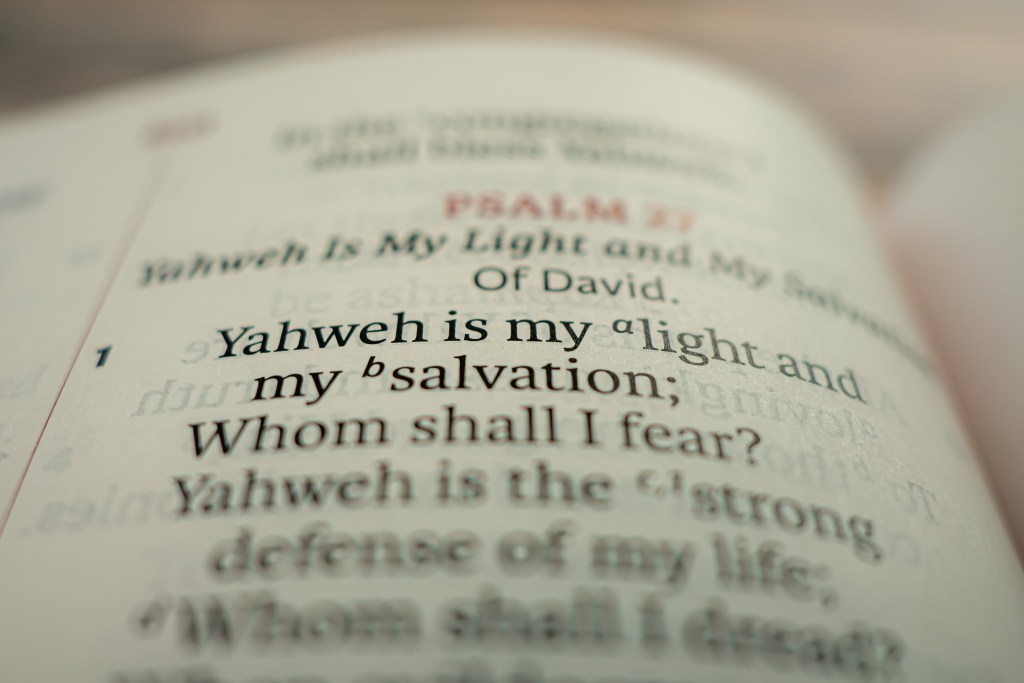

I’ve already covered that it adheres to those English versions that came before it, hence the “Legacy” in the Legacy Standard Bible. One difference is that it correctly translates the Hebrew name for God יְהוָ֞ה (Yod Hei Waw Hei – YHWH) as Yahweh. Almost all other English versions substitute the name of God with the title of God, LORD in all capitals (although the ASV of 1901 did use the name Jehovah instead of LORD). There is nothing wrong with substituting God’s name with LORD; modern Judaism does not use God’s name because it is holy, and the New Testament writers, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, used the Greek word κύριος, which means “Lord”. Nevertheless, יְהוָ֞ה (Yahweh) is the name God calls Himself when asked by Moses in Exodus 3:15 “Whom shall I say has sent me?” Plus, God’s name is used over 6,800 times in the Hebrew Scriptures. In Exodus 6, we are told that Yahweh is God’s covenant name with His people.

“Then Yahweh said to Moses, ‘Now you shall see what I will do to Pharaoh; for by a strong hand he will let them go, and by a strong hand he will drive them out of his land.’ God spoke further to Moses and said to him, ‘I am Yahweh; and I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as God Almighty, but by My name, Yahweh, I was not known to them. And I also established My covenant with them, to give them the land of Canaan, the land in which they sojourned’” (Exodus 6:1-4 LSB).

Most of us understand that in the Old Testament, when we see LORD, it means Yahweh. So, to translate it as such is simply transliterating the name of God and not substituting it. It is exactly how the Hebrew Scriptures use it. In the Scriptures, when we read the word “Hallelujah,” we are actually using God’s holy name because the word means “Praise God, Yahweh.”

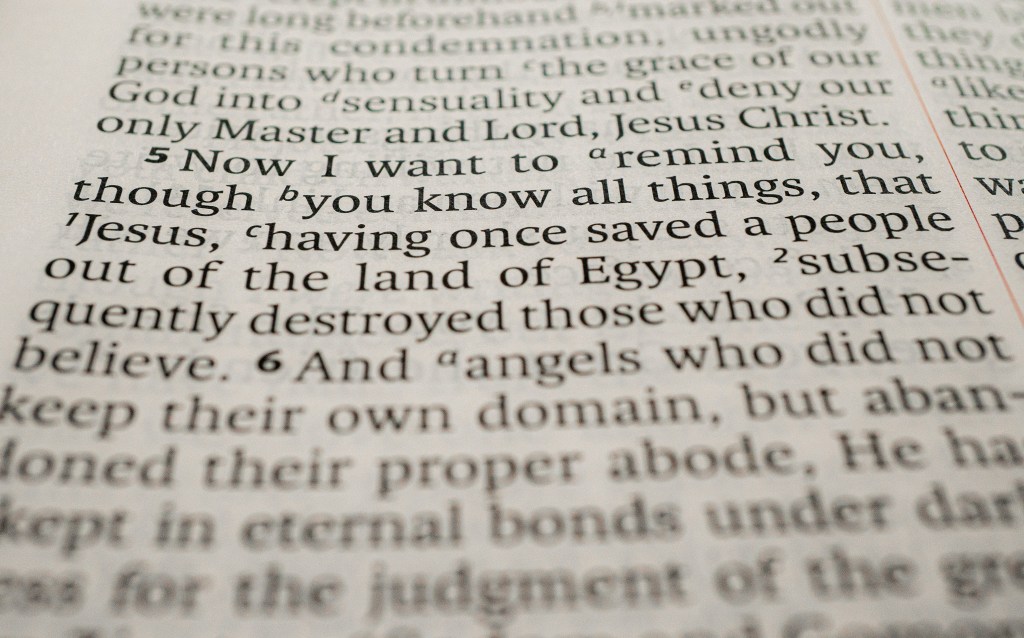

The LSB also is consistent when translating a Hebrew or Greek word. The preface to the LSB notes this and how they translate the Hebrew עבד (ebed) and the Greek δοῦλος (doulos) as “slave.” This was a risky but correct translation, considering how we view the word “slave” today in light of antebellum slavery in America. The ancient world saw slavery in a completely different light. That being said, keeping consistency in the translation helps the English reader understand how the Hebrew and Greek readers understood the Scriptures. In so doing, the LSB keeps most of the wordplay found in the original languages. For example, in Romans 6, Paul notes that before our salvation we were “slaves” to impurities and sin, but now we are “slaves” to righteousness and enslaved to God (vs. 19-22). Paul’s use of the same Greek word is sometimes overlooked when translating, but the LSB keeps the play on words by consistent translation. Likewise, in Galatians, the Greek word for “seed” is consistently translated as “seed” in verses 16 and 29. In Romans 12:3, the Greek word for “think” is found four times in that verse in Greek but is often only translated as “think” two or three times. The LSB has kept all four times it is used in that verse.

“For through the grace given to me I say to each one among you not to think more highly of himself than he ought to think; but to think so as to have sound thinking, as God has allotted to each a measure of faith.” (LSB)

Another unique and lovely feature has to do with the poetry of the Psalms. There are times when the Hebrew reader would know that each verse began with a certain Hebrew letter, a type of an acrostic. The LSB keeps those and allows the English reader to see it by starting those verses with the Hebrew letters (such as in Psalm 9, 10, 37, and 119).

The LSB, while literally accurate, is also very readable (much like the ESV or NASB20 but without some of the gender-inclusive nuances). In general, it actually seems more reader-friendly than the NASB95. And, as odd as this may seem to us, those who speak English as a second language will find the LSB more readable because of its literalness without as many modern English expressions. The LSB keeps “only begotten” instead of “One and only,” which is refreshing. In 2 Peter 1:1 (and elsewhere), we find the reading “Simeon Peter” instead of “Simon Peter.” Since the Greek reads “Simeon,” it is faithful to Peter’s name. While not an exhaustive review, these examples afford the reader the opportunity to see that the LSB is a very readable and accurate-literal translation of God’s word.

The LSB is a joint effort from the Lockman Foundation, Steadfast Bibles, 316 Publishing, Dr. John MacArthur, the Master’s University, and Seminary. In fact, there are several YouTube videos where Dr. MacArthur and the translators talk about the LSB, allowing you to meet and hear from those who did the work. This is something I have never seen from a Bible translation committee.

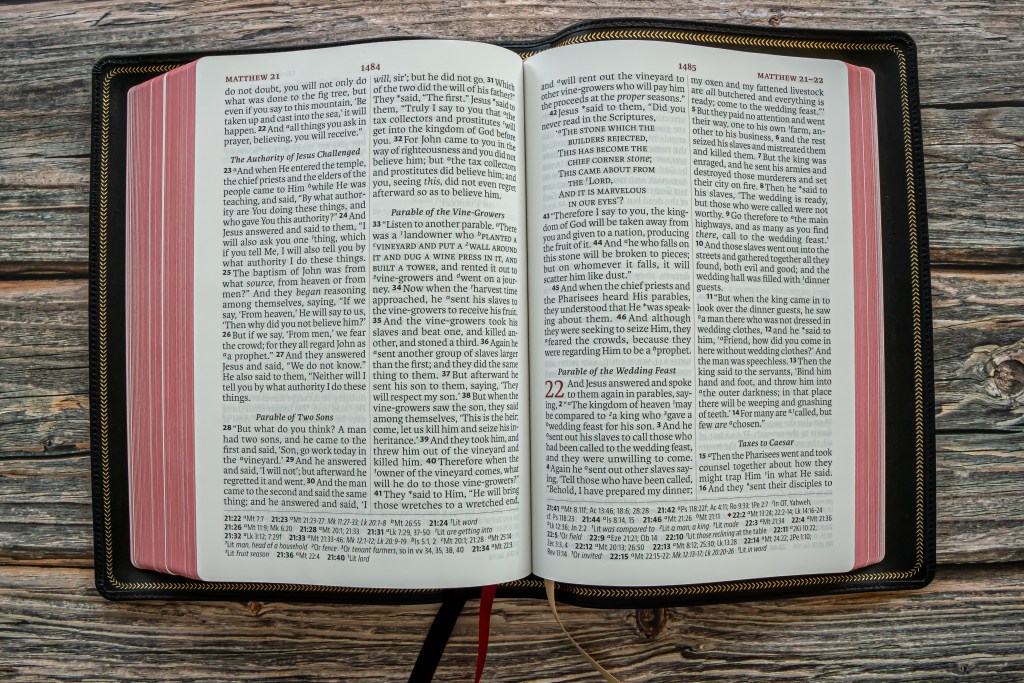

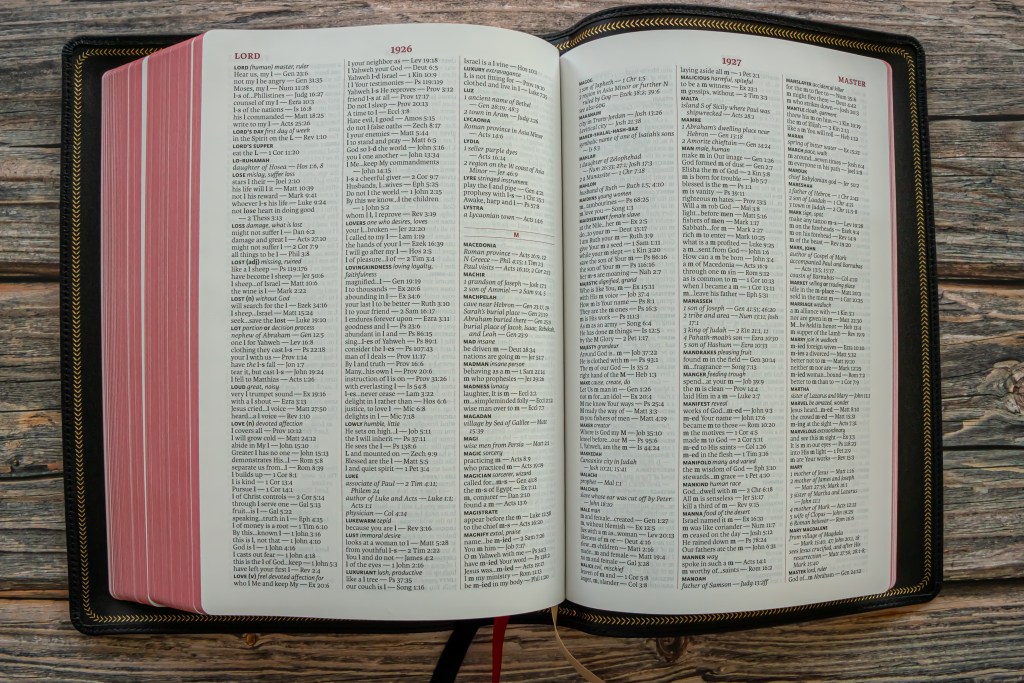

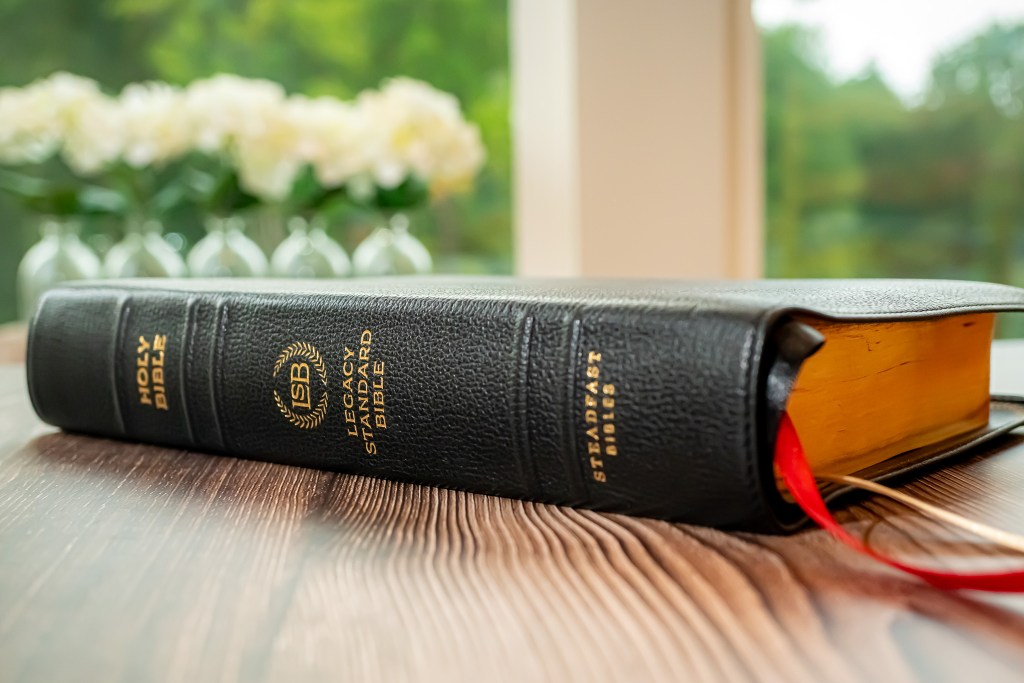

Giant Print Edition

A few weeks ago, I received the goatskin Giant Print Edition LSB. It is absolutely gorgeous. For my tired, older eyes, the 13pt. font is easy to read even without my glasses. I was concerned that it would look too big, but it doesn’t. The paper is 32 GSM and is a slight yellow which makes the black print stand out. The typesetting is by 2K/Denmark, which does the typesetting for several premium Bibles. It is lined match, and the opacity of the paper is such that you only have a slight amount of ghosting, which I don’t really notice. The ink is consistent, with book names and chapter headings in a nice red that is a great contrast to the black text of the verses.

The leather is soft and supple. It lays comfortably in your hand as if saying “this is where I belong” inviting you to eagerly engage each page. Wherever you open it, it stays open even when placed on a flat surface (although personally I love the feel of it so much I don’t want to put it down). It has red-under-gold gilding, smyth-sewn edge-lined binding with lined cowhide inside. It is premiered stitched, so this is a Bible that will last for a very long time. While mine is goatskin, there is a paste-down cowhide edition as well, and a paste-down faux leather version, and a hardcover edition. All of which have the same print and are the same on the inside. There are 95,000 cross-references and 14,000 translation footnotes. There is a concordance with 16,000 plus words, 8 full maps, a table of weights, measurements and currency.

I would like to conclude with the emblem for the Legacy Standard Bible and a mini-sermon. The LSB uses the symbol of laurel leaves which is a symbol of achievement (and the LSB certainly is that). There is more. In the ancient world laurel leaves were used in ointments for healing and for aroma. This is also appropriate in that God’s word is healing for the soul and for believers it is the sweet fragrance of the Spirit. While I doubt that all of this was intended it is true nevertheless. And, while laurel leaves were common for Greeks and Romans, they are also found in Israel – but mostly from one location, Mount Hermon. There they grow in abundance. The fact that they are from Mount Hermon brought something else special to my mind. For not only is Mount Hermon mentioned in Scripture (Psalm 89:12; 133:3; Song 4:8) there is a connection with us as believers. One day Jesus took His disciples over 25 miles north just to visit Mount Hermon. There the pagan’s had set up a temple to the Greek god Pan. There is a cave there that they called, “the Gates of Hell.” And it was there that Jesus said He would build His Church. With this in mind, what a wonderful choice for an emblem. Each time I see that ensign I am reminded that upon God’s word and through His grace I am part of that body of believers, built on the Rock – “and that Rock was Christ” (1 Corinthians 10:4 LSB).

(This is an independent brief review made without endorsement by or from Steadfast Bible.)

Leave a comment