“He is not here, for He has risen, as He said. Come, see the place where He lay.”

— Matthew 28:6

As Easter approaches, believers around the world pause to reflect on the events that changed history—the suffering, death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. While Scripture remains our ultimate authority, the Shroud of Turin remains an enigmatic artifact that many believe offers visual, forensic, and historical echoes of the Gospel narratives. In a world increasingly driven by visual evidence, perhaps this cloth still speaks.

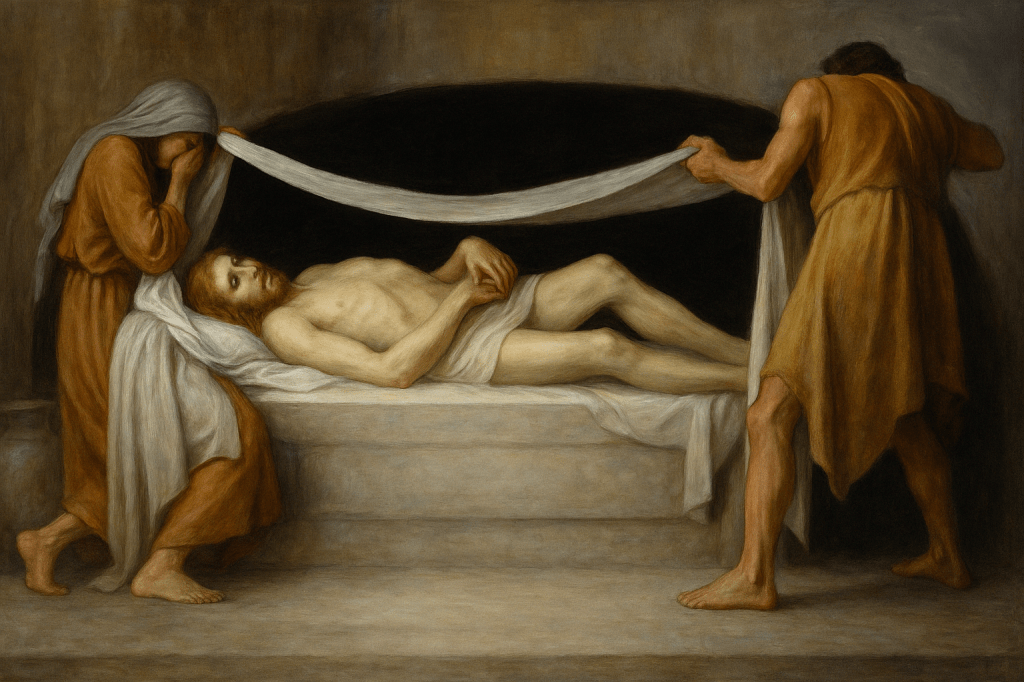

A Glimpse of the Crucified

The Shroud of Turin is a rectangular linen cloth, approximately 14.3 feet long by 3.7 feet wide. Upon it is the faint image of a man, front and back, who suffered a brutal crucifixion. Bloodstains correspond to wounds from scourging, punctures consistent with a crown of thorns, and nail marks in the wrists and feet. A large wound in the side—likely from a spear—appears to have produced a flow of both blood and clear fluid, just as John’s Gospel describes (John 19:34).

And yet, the image is not made with pigment, paint, or dye. It rests only on the topmost fibrils of the cloth’s surface and cannot be replicated using any known artistic technique, even with 21st-century tools. In fact, when photographed in 1898, the negative revealed a hauntingly realistic positive image, as if encoded in reverse long before the invention of cameras.

The 1978 STURP (Shroud of Turin Research Project) team—comprising over 30 scientists, many skeptical—concluded: “There are no chemical or physical methods known which can account for the totality of the image.”¹ In an age of skepticism, that is a powerful confession.

A Dead Man, But Not Long Dead

The man in the Shroud is without question dead. This is seen in the pooling of blood, the separation of serum and red cells (seen as a halo around the stains), and the relaxed state of the body. Yet the body shows no signs of decomposition, and rigor mortis had not fully set in—a biological process that begins within hours and reaches full rigidity by about 12 hours after death, dissipating after 36 to 48 hours.

This implies the body was laid in the cloth shortly after death and removed within 48 hours—matching perfectly the time between Jesus’ crucifixion and His resurrection on the third day.² There are no smears or disruption of the bloodstains, indicating that the body was not unwrapped or pulled out, but rather vanished or dematerialized, leaving the cloth behind.

This absence of decomposition is a silent but powerful testimony. If the cloth were fabricated, a medieval forger would not have known the timing of rigor mortis or the subtleties of serum halos—both of which were scientifically discovered centuries later.

A Burial According to Jewish Custom

The Shroud reflects Jewish burial customs, not medieval Catholic ones. According to the Mishnah, a person who suffered a violent death was not to be washed, so that their spilled blood would not be dishonored.³ This explains why the man in the Shroud was not cleaned before burial, and why blood remains on his hair and body.

The linen appears ritually clean and of high quality—consistent with Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy member of the Sanhedrin, offering his own tomb and linen for the burial of Jesus (Matt. 27:59–60). Nicodemus brought about 75 pounds of spices (John 19:39), which were likely laid around the body rather than applied to it, supporting the idea that the women who came after the Sabbath intended to complete the burial process (Mark 16:1).

Further, the Gospels mention two types of cloths:

- Sindōn (σινδών) — a large linen shroud (Matt. 27:59; Mark 15:46), matching the Turin Shroud

- Othonia (ὀθόνια) — smaller linen cloths or strips (Luke 24:12; John 20:5–7), possibly including the facial covering

This matches what we see today: a large burial cloth (the Shroud of Turin) and a possible facial cloth (the Sudarium of Oviedo), which also bears type AB blood stains and matches the wound patterns of the Shroud.⁴

No medieval artist could have intuited this distinction in Greek or reflected such accurate Jewish customs. This kind of detail is not only authentic—it’s too authentic to fake.

The Silence of Saturday, the Glory of Sunday

On Good Friday, we meditate on Christ’s passion. The Shroud visibly bears the marks of that horror—lashes from a Roman flagrum, swelling from blunt trauma, blood from thorn wounds. The body is still. The suffering has ended.

On Holy Saturday, we sit in silence. Death appears victorious. The tomb is sealed. And yet, the Shroud is silent too—not in decay or ruin, but in mystery. It holds something back.

On Easter Sunday, the silence breaks. The tomb is empty, and the Shroud remains—folded, left behind, bearing witness. In John 20:6–8, Peter and John enter the tomb and see the linen cloths. John writes that he saw and believed. The Shroud of Turin may be one of those cloths—an enduring visual echo of belief.

The Carbon-14 Debate and Five Other Clocks

Critics often appeal to the 1988 carbon-14 dating that placed the cloth between 1260 and 1390 AD. But the sample used was taken from a corner of the cloth that had been visibly rewoven in the Middle Ages—a fact confirmed by both textile experts and chemical analysis.⁵ Raymond Rogers, a chemist from Los Alamos, discovered cotton fibers and spliced threads at the sampling site, and his findings were published in a peer-reviewed journal.⁶

Beyond this, five other scientific tests suggest a much older origin:

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Raman Spectroscopy

- Mechanical Tensile Strength

- Vanillin Loss Analysis

- Radiation-Based Image Hypotheses

All of these indicate a date consistent with the first century.⁷ A fuller analysis of these methods and their implications is available in my paper Sacred Threads: The Shroud of Turin in Scriptural and Jewish Context.⁸

The Image That Shouldn’t Be There

Despite extensive efforts, no one has replicated the Shroud’s image—not with ancient tools, not with medieval chemistry, not with modern lasers. Some researchers believe a burst of energy, possibly ultraviolet light or another unknown form of radiation, may have caused the image. But even this is speculation.

Could it be that what we are left with is an image created not by human hands, but by something—or Someone—breaking the laws of biology and physics?

What Will You Do with the Evidence?

The Shroud of Turin cannot save. It does not speak. It offers no sermon, no inscription, no miraculous voice. And yet, it shows—visually and biologically—the cost of sin, the silence of death, and the possibility of resurrection.

It may be, as John wrote, that one day someone sees the cloth and believes. Or perhaps it serves merely as a signpost, urging us to re-read the Scriptures and re-encounter the Christ who conquered the grave.

Either way, this Easter, the tomb is still empty—and the Shroud still bears silent witness to the greatest event in history.

Footnotes

¹ John P. Jackson et al., “The Shroud of Turin: A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses,” 1979.

² Frederick T. Zugibe, The Crucifixion of Jesus: A Forensic Inquiry (New York: M. Evans, 2005).

³ Mishnah, Sanhedrin 6.5.

⁴ Mark Guscin, The Oviedo Cloth (Lutterworth Press, 1998).

⁵ P.E. Damon et al., “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin,” Nature 337 (1989).

⁶ Raymond N. Rogers, “Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin,” Thermochimica Acta 425 (2005).

⁷ Giulio Fanti and Pierandrea Malfi, The Shroud of Turin: First Century After Christ! (Pan Stanford, 2015).

⁸ Tom Dallis, Sacred Threads: The Shroud of Turin in Scriptural and Jewish Context, available at www.tomstheology.blog

Leave a comment