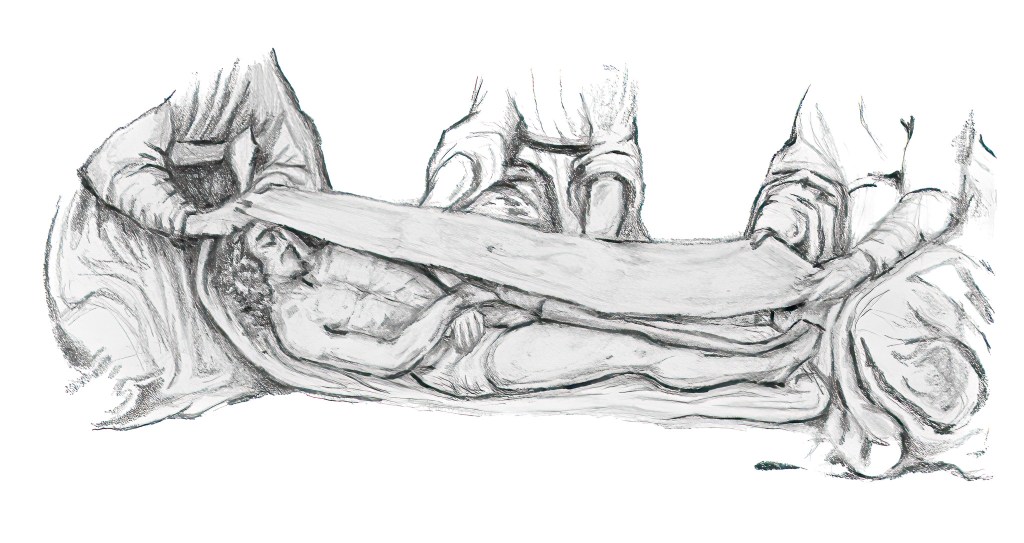

“And Joseph bought a linen shroud, and taking him down, wrapped him in the linen shroud and laid him in a tomb that had been cut out of the rock.”

—Mark 15:46

Few artifacts have captivated both the religious and scientific communities like the Shroud of Turin. While much has been said about its image, its age, and the mysteries surrounding its formation, what remains underappreciated is how remarkably it mirrors the burial customs of first-century Jews in and around Jerusalem. The Shroud is not simply a fascinating relic; it is a cultural and historical artifact that fits squarely within the Jewish practices of the late Second Temple period. In this blog, we will explore how the Shroud’s physical features, burial context, and even forensic details testify to a man not only crucified, but buried as a Jew, in accordance with Jewish law and custom.

Burial Practices in First-Century Jerusalem

Jewish burial practices during the first century were steeped in law, tradition, and theological conviction. Burial was not a matter of personal preference or aesthetic ritual. It was a sacred duty—a mitzvah—performed to honor the dignity of the deceased. According to Deuteronomy 21:23, even the body of a criminal could not be left hanging overnight. The Mishnah (Sanhedrin 6:5) reinforces this mandate, underscoring the requirement of same-day burial. Especially on the eve of a Sabbath or holy day, the body had to be removed, wrapped, and interred with reverence.

Archaeological evidence from sites such as the Mount of Olives, the Hinnom Valley, and the recently excavated Tomb of the Shroud confirms these customs. Linen shrouds were commonly used, with the body laid out flat or wrapped in a winding sheet. Additional bands of cloth were often used to tie the hands and feet, or to bind the jaw shut. Spices were used not for embalming, as in Egypt, but to honor the dead and mitigate odor. This aligns perfectly with the Gospels, which report that Jesus was wrapped in a linen cloth and laid in a new tomb, hastily but respectfully, with spices provided by Nicodemus and others (John 19:39-40).

Furthermore, rock-hewn tombs were common among the wealthier classes in Jerusalem. Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin and likely a man of means, is said to have offered his own tomb for Jesus’ burial (Matthew 27:57-60). The Shroud’s association with a rock-hewn tomb, confirmed by the limestone particles found on the cloth, strongly reinforces its consistency with this archaeological and textual backdrop.

The Man of the Shroud Appears Jewish

Many features of the Shroud align specifically with Jewish identity and burial norms:

- Burial with Blood Intact: Jewish law required that blood lost through violence be buried with the person, as blood was seen as part of the soul (Leviticus 17:11). The Shroud displays bloodstains at the scalp, wrists, side, and feet, consistent with crucifixion and scourging. There is no sign of decomposition, suggesting that the body was removed from the cloth within 36 to 40 hours—again, consistent with the Gospel account.

- Absence of Pagan Embalming: The body shows no signs of embalming or internal treatment. Pagan and Roman customs often included artificial preservatives or display preparations. Jewish customs, by contrast, insisted on simplicity, modesty, and the prompt return of the body to the earth.

- Textile Evidence: While the Shroud’s herringbone weave is rare, it is not unknown. Textiles with advanced weaves have been found at Masada and in Roman contexts. Such a weave would be plausible for a high-status burial, particularly one provided by a wealthy individual like Joseph of Arimathea. Importantly, the cloth is made of linen, not wool, consistent with Jewish purity laws that forbid mixing fibers (Deuteronomy 22:11).

- The Sudarium and Burial Bands: John 20:7 describes a separate cloth used to cover Jesus’ face. Jewish custom included the use of a face cloth (sudarium) and bindings. In cases of violent death, the goal was to preserve all body parts and fluids. The presence of a separate facial cloth aligns with Jewish efforts to preserve dignity and blood integrity. The Sudarium of Oviedo, which has blood stains matching the Shroud, fits this well. The Sudarium would have been removed from the face if blood soaked out of respect for the deceased.

- Rock-Hewn Tomb and Sabbath Compliance: Burial in a tomb cut from rock, as described in the Gospels, was standard for Jerusalem’s upper class. The urgency to bury Jesus before sundown on the eve of Passover further confirms strict Sabbath observance, a hallmark of Jewish identity.

- Use of Spices: The Gospels speak of seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloes. This would have been a kingly amount, used to anoint and honor the dead. Chemical analysis of the Shroud confirms traces of these substances.

- Position of the Body: The man in the Shroud lies with his hands crossed at the pelvis. This is not typical Roman display positioning but reflects reverent placement. The feet appear bound, and the overall alignment mirrors practices found in Jewish ossuary burials, where bodies were laid out before secondary interment.

- Traditional Hair and Beard of a Nazarite (and Fulfillment of Prophecy): The Shroud depicts a man with long hair parted in the middle and falling toward the shoulders, as well as a full beard and what appears to be a tied ponytail at the back. This hairstyle is consistent with Jewish customs, particularly for those who had taken a Nazarite vow. According to Numbers 6:5, a Nazarite was forbidden from cutting his hair during the period of consecration—a period which, in this case, appears to have lasted approximately three and a half years. Forensic studies confirm that shoulder-length hair and an average full beard would reflect such a duration of uncut growth (see Sacred Threads, pp. 60-64). Additionally, there are areas on the Shroud, particularly around the chin, where the beard appears to have been ripped out—consistent with the prophecy in Isaiah 50:6, “I gave my back to those who strike, and my cheeks to those who pull out the beard.” This brutal detail not only supports the suffering endured by the man of the Shroud, but further confirms the convergence of historical Jewish practice and messianic expectation embedded in this burial cloth.

Burial Customs Affirmed by Archaeology

The Tomb of the Shroud, discovered in the Hinnom Valley, is one of the most important archaeological parallels to the Shroud of Turin. The tomb contained a linen burial cloth dated to the first century, wrapped around a man who had leprosy. The presence of a burial shroud, head cloth, and aromatic resins confirms that such cloths were used and preserved, at least under ideal conditions. Moreover, discoveries at Qumran and in the Jerusalem necropolis reinforce the use of individual shrouds and cloth bindings, contradicting those who claim the Shroud’s practices were foreign to the region.

What makes the Shroud exceptional is not that it deviates from first-century Jewish norms, but that it reflects them so precisely. A medieval forger could not have anticipated modern archaeological discoveries, nor could he have known the burial laws recorded later in the Mishnah and confirmed through excavation. The accuracy with which the Shroud mirrors Jewish burial practices is, in itself, evidence against it being a fraud.

A Burial Unlike Any Other

Yet something about this burial is unique. The image itself. Not painted, not etched, but somehow residing only on the outermost fibrils of the linen. No brush strokes, no pigment. A negative image that encodes three-dimensional spatial data—something that would not be discovered until the 20th century. The Shroud is not just a relic; it is a forensic mystery. But one rooted deeply in Jewish tradition.

The man was wrapped in a ritually clean cloth. He was buried in haste but with reverence. He bore the wounds of a Roman crucifixion, yet was treated according to Jewish law. He was buried before the Sabbath. His blood was preserved with his body. There are no signs of decay. And then, something happened. Something that left a faint image without damaging the cloth. Something that neither ancient nor modern technology can replicate.

History, Identity, and Mystery

The Shroud of Turin is more than a sacred curiosity. It is a cloth woven into the very history of first-century Judaism. Its fibers whisper of a world where the law was honored, death was reverenced, and burial was sacred. It reflects the world of Jerusalem’s tombs, of purity rituals and Passover urgency. And within its image lies the testimony of a man who died a brutal death and was buried as a faithful Jew.

Was he Jesus of Nazareth? The evidence aligns. The wounds, the burial, the timing, the tomb, and the image—all match the Gospels.

But even apart from faith, the Shroud stands as the most Jewish burial cloth ever found. And perhaps that is no coincidence.

Secred Threads, www.tomstheology.blog

Leave a comment