Why Ignoring Ancient Context Is Not Just Unfair, but Unethical

The Bible is the most read, translated, and debated text in human history. But it is also among the most misread. Often, people quote Scripture as if it dropped out of the sky in English with chapter and verse divisions, ready-made for modern application. This flattening of the text—a willful ignorance of its cultural, linguistic, and historical roots—is more than a misstep. It is an ethical failure. When Scripture is used in this way to support ideologies, fuel debates, or win arguments, it is no longer being interpreted—it is being exploited.

Proper biblical interpretation is not merely a technical exercise for scholars; it is a moral obligation for every serious reader. It requires humility, honesty, and the willingness to admit that our world is not the same as the world of ancient Israel or first-century Palestine. To interpret responsibly is to honor the God who spoke through real people in real times and places.

Importantly, this obligation is not limited to Christians. Atheists, agnostics, and skeptics who engage with the Bible publicly—whether in criticism, mockery, or academic rebuttal—bear the same ethical responsibility to represent the text fairly. Misrepresentation is not excused by disbelief. If one claims to expose the Bible’s flaws, one must first represent it accurately. Anything less is a form of intellectual slander.

1. Scripture Has a Cultural Context—It’s Not Optional

To read the Bible without regard for its cultural context is like trying to understand Shakespeare without Elizabethan English or ancient Egyptian art without hieroglyphics. Scripture is embedded in the soil of the ancient Near East and the Greco-Roman world. It speaks the language of patriarchal kinship structures, ritual purity, temple worship, patronage systems, and oral transmission of wisdom.

John H. Walton famously clarifies, “The Bible was written for us, but not to us.” This isn’t a mere slogan. It’s a hermeneutical axiom. The Bible’s truths transcend culture, but they are communicated through it. Ignoring this leads to serious theological errors. For instance, interpreting the Genesis creation account as modern science was never the intent of the Hebrew author. It was an ancient cosmology written in dialogue with the Babylonian worldview.

When Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit” (Matt. 5:3), we might imagine financial poverty or emotional humility. But in Jesus’ world, this beatitude evoked dependence on God in a social order where status meant everything. Without honor, you had no place. The original hearers heard not sentimentality but revolution.

Failing to recognize context risks replacing divine revelation with modern projection. As theologian Kevin Vanhoozer puts it, “We must not confuse the Word of God with our interpretations of it.”

Skeptical Missteps: Many atheist critics fall into the same trap by critiquing texts with no regard for ancient genres or worldview. For example, Richard Dawkins famously dismisses Old Testament narratives as evidence of a “morally repugnant deity” but makes no attempt to contextualize concepts like divine kingship, ancient treaty structures, or Near Eastern hyperbole.¹³ The same mistake occurs when skeptics cite Leviticus out of context to discredit Christian ethics—forgetting that these were laws for ancient Israel, not Christian instruction manuals. In doing so, they often resemble the fundamentalists they claim to oppose.

2. Ethical Interpretation Requires Intellectual Honesty

There is a line between ignorance and manipulation. The first can be corrected by teaching; the second is a matter of character. To persist in an interpretation after being shown its historical or linguistic errors—because it suits one’s theology or argument—is dishonest. It turns the Bible into a prop, not a revelation.

This is what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace,” not in terms of salvation, but in terms of exegesis—grabbing a comforting text without wrestling with its demands. It is also what Miroslav Volf critiques as “textual tyranny,” when Scripture is made to say what we want rather than what it intends.

Take Romans 13, often quoted to justify governmental power. Without context, it becomes a blanket endorsement of authoritarianism. But Paul was writing in a Greco-Roman world, under Caesar Nero, about the need for Christian witness in public order—not endorsing tyranny.

Intellectual honesty demands we ask: “What did this mean then?” before we ever ask, “What does it mean now?” Without that first question, we risk the sin of bearing false witness—not just against our neighbor, but against God’s Word.

Skeptical Missteps: Skeptics regularly apply modern moral frameworks to ancient texts without acknowledging the difference in context or values. Bart Ehrman, for instance, often treats biblical inconsistencies as irreconcilable contradictions, even when literary scholars have shown that such variations are common in ancient biographical writing (bios).¹⁴ His approach can mislead readers into thinking the Gospels are inherently deceptive or sloppy when, in context, they follow recognized narrative conventions of the time.

3. Misusing the Bible Has Tangible Harm

Scripture wielded without understanding is not harmless—it is dangerous. History is littered with examples of how poor exegesis led to violence, marginalization, and injustice. The medieval church used Luke 14 to justify forced conversions. American slaveholders cited Ephesians 6:5 to defend slavery. Women were silenced with 1 Corinthians 14:34, while ignoring the cultural practices Paul was responding to. These were not errors in grammar. They were errors in ethics.

Context helps us recognize hyperbole, poetry, metaphor, idiom, and rhetoric. It helps us distinguish between divine prescription and human description. Without it, we collapse the world of the text into our own and weaponize Scripture for our cause.

As Mark Noll wrote, “The scandal of the evangelical mind is not only that it lacks a mind—it has also too often lacked memory and humility in its reading of Scripture.” To misread the Bible is to risk misrepresenting God. There is no greater harm.

Skeptical Missteps: Some atheists have used Scripture to argue that Christianity causes social harm—without distinguishing between misuse of the text and faithful interpretation. The “God Delusion” line of attack often lumps together every misuse of the Bible as proof of its inherent toxicity. This is historically dishonest. Critics don’t blame medicine for malpractice; why blame Scripture for distortion? To conflate abuse with essence is itself an ethical misrepresentation.

4. The Context Group and the Call for Cultural Literacy

The Context Group, a collective of scholars like Bruce Malina and John Pilch, has spent decades helping modern readers see the social and cultural frameworks of Scripture. Their studies show that honor-shame societies, not guilt-innocence ones, shaped biblical ethics. They demonstrate how collectivist identity, not individualism, was the default social unit. These insights are not distractions—they are keys.

When Paul speaks of being a “slave of Christ” (Rom. 1:1), we interpret that through modern eyes of servitude and abuse. But Paul’s audience would hear a language of loyalty, household status, and patron-client relationships. To call Jesus “Lord” was not just pious—it was politically subversive.

Without cultural literacy, we make the Bible say things it never said and ignore what it actually meant.

Skeptical Missteps: Popular online memes often ridicule biblical commands without even attempting cultural understanding. For example, mocking the command not to “mix fabrics” (Lev. 19:19) as a moral absurdity shows ignorance of its original context—namely Israel’s symbolic separation from pagan practices. Such ridicule is often taken at face value by thousands, reinforcing caricature rather than fostering genuine dialogue. In doing so, skeptics commit the very hermeneutical sins they accuse Christians of.

5. Shouldn’t Scripture Be Clear Enough?

It’s fair to ask: Shouldn’t God make His Word plain? If the Bible needs so much historical background, doesn’t that undermine its clarity?

In response, we must distinguish between clarity of message and clarity of meaning. The gospel is clear—Christ died, was buried, and rose again. But that message comes through stories, poetry, apocalyptic symbols, genealogies, parables, and letters, all deeply embedded in ancient life. God could have written Scripture as a systematic theology textbook, but He chose to inspire real people in real cultures.

Even Jesus taught in parables, not formulas. He drew from first-century agrarian life to communicate truths about the Kingdom. Context isn’t an obstacle—it’s part of the method.

Understanding the Bible’s context is an act of love: love for the text, love for the author, and love for those who have been shaped by misreadings.

Skeptical Missteps: The assumption that the Bible should be clear by modern standards leads many skeptics to claim that ambiguity disproves divine authorship. But this presumes a modern epistemology, expecting Scripture to behave like a lab manual or philosophy textbook. In truth, Scripture reflects the complexity of real history, real emotion, and real human experience. Demanding it conform to our preferences says more about us than about God.

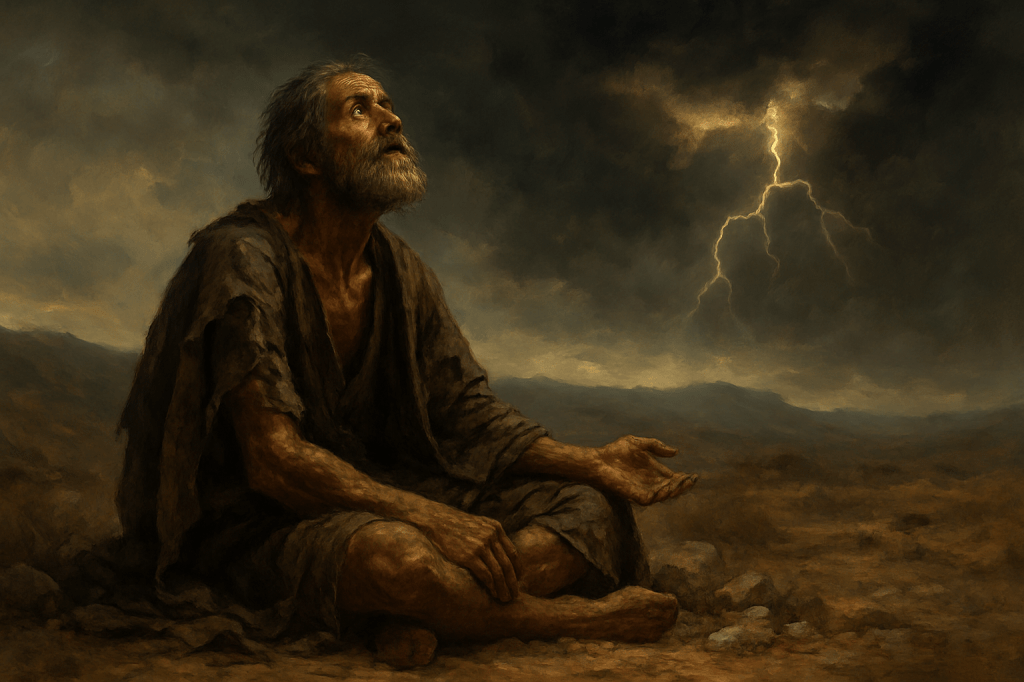

6. A Word on Job: Misreading Suffering, Misrepresenting God

Before we turn to the ethical weight of biblical interpretation, it’s worth pausing on one of the most misread books in all of Scripture: the Book of Job. This profound text is often weaponized by skeptics and misunderstood by believers alike—not because of what it says, but because of what we assume it should say.

We come to Job asking, “Why does God allow suffering?” expecting a tidy theodicy, a rational justification for pain. But that is not the question Job is meant to answer. The book doesn’t offer easy explanations; instead, it undermines our demand for them. It challenges the assumption that suffering always fits neatly into divine justice formulas. It exposes the limits of human wisdom, and—most strikingly—it rebukes those who speak confidently on behalf of God without understanding His purposes.

And yet, how often do we become like Job’s friends—believers and skeptics alike—offering mechanistic explanations or cold critiques, when the better response is silence, presence, or lament?

Skeptics frequently misuse Job to portray God as cruel or cavalier: a deity who casually permits Satan to torment a faithful man. But this interpretation ignores the literary structure, the heavenly courtroom motif, and the final divine speeches. Job’s suffering is never trivialized by God. In fact, it is Job—not his friends—whom God vindicates, precisely because he refuses to reduce God to a simplistic moral equation.

Ironically, those who mock the book for its portrayal of suffering often mirror the very friends that God condemns: they speak of God without knowledge. They demand moral clarity on their own terms and then accuse God of failure when He does not submit to their system. But the final chapters of Job offer no neat answers. They offer something better: the presence of God and a call to humility in the face of mystery.

The lesson of Job is not “Here is why good people suffer.” The lesson is, “You are not God. Do not speak too quickly on His behalf.” This is not just a theological warning. It is a moral one. Job reminds us that even the most sincere explanations can become dangerous when detached from reverence, context, and humility. And it is precisely that posture—humble, attentive, cautious—that should guide every approach to Scripture.

7. The Ethical Imperative: Responsibility Before Interpretation

We are stewards of the Word, not owners. The Bible is not ours to manipulate. It is God’s voice through ancient testimony. If we are to “rightly divide the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15), we must do so with reverence for its context, not convenience for our arguments.

As Richard Hays argues, “Faithful interpretation must be governed by the moral vision of Scripture itself.” That moral vision includes truth-telling, humility, and a willingness to be corrected.

We would not tolerate a journalist who misquotes a source or a lawyer who twists a witness’s words. Why then do we excuse it in theology? To interpret Scripture is to walk on holy ground. To ignore its cultural world is not just clumsy—it is unethical.

Skeptical Missteps: Skeptics who quote Scripture for rhetorical attack often show little concern for context or nuance. When memes circulate calling God “genocidal” based on conquest texts in Joshua, they typically ignore the ancient war rhetoric common to all cultures of the time, or the archaeological and literary evidence suggesting hyperbole. One cannot claim to champion truth and simultaneously caricature the very text being critiqued.

Endnotes:

- John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009).

- Peter Enns, Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005).

- Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008).

- Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Is There a Meaning in This Text? (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998).

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship (New York: Touchstone, 1995).

- Miroslav Volf, A Public Faith (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2011).

- N.T. Wright, Paul for Everyone: Romans, Part 2 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005).

- Mark A. Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994).

- Bruce J. Malina and John J. Pilch, Social-Science Commentary on the Letters of Paul (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006).

- David A. deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship & Purity (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2000).

- C.S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1958).

- Richard B. Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996).

- Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006).

- Michael R. Licona, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Leave a comment