Why Reality Itself Points to God

What if the universe only exists because it is being watched?

“No phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon.”

That’s a quote from physicist John Archibald Wheeler, as cited in The Matter Myth by Paul Davies and John Gribbin.

This isn’t just a poetic quip—it’s the foundation of one of the most mind-bending implications in quantum physics: reality, at its deepest level, seems to require observation to become real.

In quantum mechanics, particles exist in a state of superposition—meaning they embody all possible outcomes—until they are observed. The act of observation collapses that wave function into one actual result. This is not a speculative theory; it’s confirmed by experiments like the double-slit experiment, where particles act like waves when unobserved, and like particles when observed.

This leads to a powerful question: if observation is required to bring about definite reality, then who or what was observing the universe before conscious beings evolved?

The Argument from Quantum Observership

- In quantum mechanics, physical systems exist in a superposition of potential outcomes until observed.

- Observation is not merely epistemic—it plays an active role in determining actualized outcomes.

- Only conscious minds possess intentionality—the capacity to direct attention and interpret information.

- Therefore, the emergence of actualized reality logically presupposes a conscious observer.

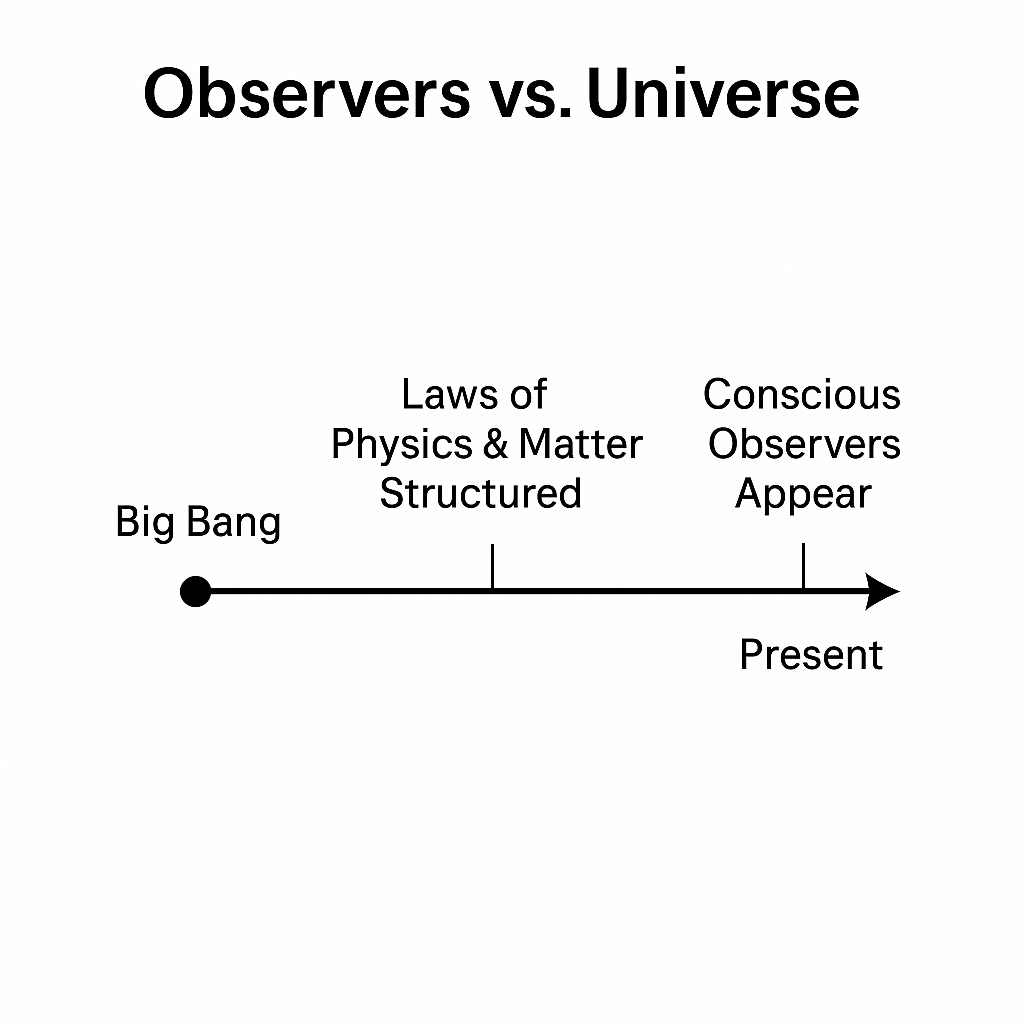

- But humans and other observers arose only after the universe already had structured laws and definite properties.

- Therefore, there must have existed a prior Observer, capable of collapsing quantum potentialities before any finite consciousness existed.

- This Observer must be timeless, immaterial, conscious, maximally rational, and metaphysically necessary.

- These attributes align precisely with the classical concept of God.

- Furthermore, this hypothesis is superior to alternatives like Many Worlds, instrumentalism, or panpsychism in terms of explanatory power, coherence, and parsimony.

- Therefore, the most reasonable explanation for a coherent, observer-dependent universe is the existence of a necessary, eternal, conscious Mind—God.

Expanding the Logic: Why Each Step Points Unmistakably to Mind

1. In quantum mechanics, all physical systems exist in a superposition of potential outcomes until a measurement or observation occurs.

This is not fringe speculation—it’s at the heart of the most experimentally confirmed theory in physics. Until observed, particles are not in one state or another; they are described by a wave function representing many possibilities simultaneously.

2. The act of observation plays an ontologically active role—it is not merely epistemic (about what we know), but metaphysical (about what exists).

Observation doesn’t just reveal a pre-existing fact; it determines the fact. This upends the classical view that the universe is fully objective and detached from the observer. The observer participates in the outcome.

3. Only conscious minds possess intentionality—the capacity to direct attention and interpret outcomes meaningfully.

Machines can register events, but only minds can interpret them. Consciousness is not incidental—it’s uniquely qualified to complete the quantum act of observation, giving “collapse” meaning.

4. Therefore, the emergence of definite, actualized states within the universe logically presupposes at least one conscious observer.

If physical states require observation to become real, and if only minds can perform meaningful observation, then the existence of an actualized universe demands a conscious agent.

5. But humans and other known observers arose only after the universe already had structured laws and resolved quantum states.

Conscious beings capable of collapsing quantum states did not exist in the earliest moments of the universe. Yet the universe then already obeyed definite laws and contained structured matter—suggesting observation had already occurred.

6. Therefore, there must have existed a prior Observer, capable of collapsing quantum potentialities before finite consciousness emerged.

This isn’t theological overreach—it’s logical necessity. If no finite mind was present at the origin of definite reality, a non-finite mind must have been.

7. This Observer must be timeless, immaterial, conscious, maximally rational, and metaphysically necessary.

Time, space, and matter began with the universe. The Observer who precedes and actualizes it must transcend all three, possess intelligence, and exist necessarily rather than contingently.

8. These attributes align precisely with the classical concept of God.

This is not redefining God to fit quantum theory—it’s discovering that the kind of being required to explain observer-dependent reality matches the God of classical theism: eternal, immaterial, intelligent, and necessary.

9. Furthermore, this hypothesis is superior to alternatives like Many Worlds, instrumentalism, or panpsychism in explanatory power, coherence, and parsimony.

Multiverse theories multiply unprovable entities. Instrumentalism evades ontology. Panpsychism sneaks in mind without metaphysical roots. Theism is simpler, deeper, and more coherent with both the data and reason.

10. Therefore, the most reasonable explanation for a coherent, observer-dependent universe is the existence of a necessary, eternal, conscious Mind—God.

It’s not a leap—it’s the logical destination. God is not an optional add-on to physics; He is the foundational Observer who makes physics possible.

Quantum Mechanics and Observation

Quantum theory is the most successful model in the history of physics—but it raises deep philosophical challenges. Chief among them is the role of the observer.

Eugene Wigner, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist, said:

“It was not possible to formulate the laws of quantum mechanics in a fully consistent way without reference to consciousness.”

That’s from his essay “Remarks on the Mind-Body Question,” published in The Scientist Speculates in 1962.

John Wheeler extended this thinking with his “participatory universe” model, arguing that the universe emerges through observation.

So the natural question follows: Before conscious beings arrived, what was observing the universe into actuality?

Fine-Tuning and Observers

We also know the universe is finely tuned. Constants like the force of gravity, the charge of the electron, and the rate of expansion had to be precisely what they are to allow for life.

Yet, quantum mechanics teaches that observers are needed for reality to resolve—while at the same time, observers can’t exist without fine-tuning.

So which came first? The observer or the observable universe?

Some invoke the Many Worlds Interpretation, claiming all outcomes happen in parallel universes. But this view is unprovable and metaphysically bloated. Roger Penrose, a physicist not known for theism, criticized this approach, saying:

“It’s an extravagant claim to say that every possible outcome of every quantum measurement actually exists.”

Others appeal to decoherence, where quantum systems interact with their environment. But even Wojciech Zurek, a pioneer in decoherence theory, admits that it doesn’t explain why only one outcome is experienced—only that interference disappears.

Some might turn to the Bohmian Interpretation—a deterministic model where particles have definite positions guided by a “pilot wave.” But Bohmian mechanics still relies on the wave function, and thus inherits the central mystery: why does the wave function have the structure it does? More importantly, Bohm’s theory introduces a non-local hidden variable—a guiding mechanism that has no classical counterpart and still requires explanation. It may restore determinism on the surface, but it does not eliminate the deeper metaphysical question: why is this one configuration actualized at all? Without a transcendent Mind, even a deterministic universe remains unexplained in its actuality.

Then we have Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiments, which show that measurements made in the present can affect what we observe in the past. This suggests that observation may not be constrained by linear time.

And Wheeler’s “It from Bit” proposal goes further: that information, not matter, is the foundation of reality—and that binary decisions shape the cosmos. But information only has meaning if interpreted—which requires mind.

Philosophical and Theological Integration

This aligns with the Principle of Sufficient Reason: for anything that exists, there must be a reason it exists the way it does. Random quantum collapses without explanation violate this principle—unless grounded in a conscious, rational source.

Also, only minds have intentionality—the quality of being “about” something. So if reality arises through observational choice, it must be grounded in mind.

John Polkinghorne, physicist and Anglican theologian, wrote in his book Quantum Physics and Theology:

“Quantum theory has undermined naive materialism, and replaced it with a view of reality much more hospitable to theism.”

Even physicist Bernard d’Espagnat, who did not identify as a traditional theist, wrote that:

“. . . the doctrine that the world is made up of objects whose existence is independent of human consciousness turns out to be in conflict with quantum mechanics and with facts established by experiment.”

That admission comes not from faith, but from physics.

Objections and Responses

Objection One: “Observation doesn’t require consciousness—machines do it.”

Response: Detectors register data, but they don’t interpret it. Without consciousness, measurement results don’t collapse into meaning.

This ties directly into what philosophers and neuroscientists call the hard problem of consciousness: subjective experience cannot be reduced to physical processes alone. Even materialists admit that how and why brain states give rise to awareness is still unsolved. If consciousness is fundamental to resolving quantum reality, as some interpretations suggest, then consciousness itself is not an emergent quirk—but an ontological primitive. This aligns naturally with the idea that a foundational Mind grounds reality.

Physicist Henry Stapp, in his book Mindful Universe, puts it bluntly:

“The role of the observer in quantum mechanics is not optional; it is essential.”

Objection Two: “Isn’t this just a God-of-the-gaps argument?”

Response: Not at all. We’re not filling ignorance with God. We’re taking the best-known features of reality—quantum mechanics, fine-tuning, intentionality—and asking: What best explains them? God isn’t filling a gap; He’s supplying the ground.

Objection Three: “This sounds more philosophical than scientific.”

Response: Yes—and that’s a strength, not a flaw. All science relies on philosophical assumptions. As physicist Paul Davies writes in The Mind of God,

“It may seem bizarre, but in my opinion science offers a surer path to God than religion.”

Even the Simulation Hypothesis, popularized by Nick Bostrom, admits that consciousness could be foundational and that our world could be an informational structure created by a mind. That’s a rebranded form of theism.

Objection Four: If God is the ultimate Observer and sees everything, then why don’t all quantum experiments—like the double-slit experiment—always yield collapsed results, even when no human observer is present? If God is always watching, shouldn’t the wave function always be collapsed?

Response: This objection misunderstands the nature of “collapse” and the difference between God’s eternal observation and a physical measurement process.

First, God’s observation is ontological, not procedural. That means His awareness upholds the very being and coherence of the universe—it ensures that the laws of physics hold, that particles behave consistently, and that the cosmos is intelligible. But this is not the same as the specific, localized measurement required to collapse a quantum system in an experiment. God’s sustaining knowledge keeps the world existent and ordered—it doesn’t override the probabilistic structure of quantum systems designed for finite observers.

Second, collapse is about epistemic resolution. It’s not triggered by the mere existence of a conscious mind but by the interaction of a system with an observer within the physical framework—often via detectors or conscious awareness. God’s omniscient knowledge exists outside the created system. It is not entangled with the quantum setup in the way needed for a wave function to collapse in time and space.

Third, many theistic models of reality affirm contingency and freedom. Just as God knows our choices without predetermining them, He can know all quantum outcomes without collapsing them Himself. He allows finite minds the meaningful role of interaction within creation—including the resolution of quantum possibilities. This doesn’t diminish His sovereignty; it reveals a cosmos built for relationship and discovery.

Finally, in all major quantum interpretations, collapse depends on physical entanglement or environmental decoherence, not metaphysical omniscience. A photon doesn’t collapse simply because a mind knows it exists—it collapses when it interacts with a detector or becomes entangled with an environment that records its state.

In summary, this objection conflates divine omniscience with physical measurement. God’s eternal observation sustains the universe’s existence and intelligibility. But wave function collapse, as understood in quantum mechanics, occurs through specific, localized interactions within time and space. Theism explains why the system exists and is coherent. Finite observers explain how outcomes become definite within that system.

A Universe That Knows Itself

Wheeler famously said:

“The universe does not exist ‘out there’ independent of us. We are inescapably involved in bringing about that which appears to be happening.”

This resonates with Genesis 1, where God speaks creation into being. It echoes John 1, where “In the beginning was the Word,” or Logos. And it aligns with Hebrews 1:3, which says God “sustains all things by His powerful word.”

Church Fathers like Augustine and Aquinas taught that God’s ideas are the archetypes of creation. Aquinas called God Pure Act—the one who actualizes all potential. What quantum physics reveals, theology anticipated.

Challenge to the Skeptic

So let’s ask plainly:

If not God, what?

What kind of entity could observe the universe into being before any finite mind existed?

Not many worlds—they’re untestable.

Not decoherence—it doesn’t resolve collapse.

Not simulation—it assumes mind.

If not an eternal Observer, what explains the collapse of the universal wave function?

Conclusion

Arguments of this kind do not claim deductive certainty. Instead, they offer abductive strength—an inference to the best explanation. That’s how science works. That’s how history works. And it’s how rational belief in God can work too. This argument doesn’t prove God like a math equation. But it gives us a powerful, interdisciplinary, rational inference:

- Observation is needed to make reality real.

- Observers need fine-tuning.

- And something must have observed before we ever could.

That “something” is not just anything. It is a timeless, immaterial, conscious, necessary Mind.

This is not the God of the gaps. It’s the God of the groundwork.

Wheeler was right: we are involved in what appears to be happening.

And Scripture echoes with finality:

The first voice that ever spoke was not heard. It was the voice that made hearing possible.

So we must choose: is consciousness a late, accidental byproduct of blind forces? Or is it woven into the structure of reality from the very beginning? If the universe is truly observer-dependent, and consciousness is irreducible, then the Mind behind the cosmos is not only possible—it is unavoidable. The collapse of the wave function is not the end of the argument. It is the beginning of wonder. And wonder, rightly pursued, leads us home.

Endnotes:

- Wheeler quote from The Matter Myth by Davies and Gribbin.

- Wigner’s statement in “Remarks on the Mind-Body Question,” found in The Scientist Speculates, 1962.

- John Polkinghorne, Quantum Physics and Theology, Yale Press, 2007.

- Henry Stapp, Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer, Springer, 2007.

- Paul Davies, The Mind of God: The Scientific Basis for a Rational World, Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Wheeler, “Law Without Law,” in Quantum Theory and Measurement, Princeton University Press, 1983.

Leave a comment