(From my lecture presentation on this subject)

The Face of Jesus: As seen in the Shroud of Turin and the Veil of Manoppello

Thank you so much for being here today. I know this isn’t your typical church talk or history lecture—but what we’re about to explore might just challenge both.

Let me take a moment to introduce myself. I studied theology at Cedarville University and Emmanuel Theological Seminary, then went on to do postgraduate work in Jewish culture from the Israel Bible Center, and Shroud studies from the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum in Rome. I also run a blog called Tom’s Theology. But let me say this upfront—I’m not here today as a scholar trying to impress you with degrees or research. I’m here as a witness to what I’ve found.

We’re going to look at two ancient cloths. One may hold the image of a crucified man. The other, His living face. These aren’t just religious relics. They’ve been studied by physicists, pathologists, textile experts, botanists, and historians—and they still defy easy explanation.

Now, I’m not here to prove anything beyond all doubt. But I do want to ask you to consider this: what happens when history, science, and faith all seem to be pointing in the same direction?

So let’s take a closer look together. Because these cloths might just be silently asking each one of us the same question: Who do you say I am?

Let’s take a look at Galatians 3:1. Paul writes, ‘O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? It was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified.’

Now think about this for a second—Paul wasn’t writing to people in Jerusalem. The Galatians weren’t eyewitnesses to the crucifixion. So what exactly did he mean by ‘publicly portrayed’?

Some scholars think Paul was using strong, dramatic language to describe how clearly the Gospel had been preached to them. And I think that’s part of it. But let me ask: what if there was more? What if there was something they could literally see—a visual echo of the crucifixion that survived from that time? Something early Christians could look upon—and something we still can?

This is the Shroud of Turin. It’s faint, but look closely. You’ll see the front and back image of a man who’s been beaten, scourged, crucified, and pierced in the side. Here’s the remarkable part—there’s no paint. No brush strokes. The image only rests on the very top surface of the linen fibers—so thin it’s less than a thousandth the thickness of a human hair. And yet it shows details even medieval artists didn’t understand: the nails through the wrists instead of the palms, bruising on the face, the exact pattern of scourge marks, swelling around the cheekbone.

This wasn’t made to inspire art. It wasn’t stylized. It’s raw, almost clinical—like a forensic photograph… centuries before photography existed.

When we look at the back of the man on the Shroud, something immediately stands out. There are over 100 distinct wounds from scourging. You can actually see the patterns—dumbbell-shaped markings made by a Roman flagrum, a whip with multiple leather thongs tipped with lead or bone.

What’s even more remarkable is the direction of the wounds. They’re not random. There are two distinct angles to them, suggesting two soldiers—one on each side—taking turns, just as ancient Roman accounts describe.

There are no artistic flourishes here. No exaggerated blood trails, no stylized wounds. What we see is anatomically correct, consistent with what medical experts now understand about scourging. These are details medieval Europe simply didn’t know.

It’s painful. It’s brutal. And yet it aligns perfectly with what the Gospels record. This is what Isaiah was pointing to when he wrote, ‘By His stripes, we are healed.’

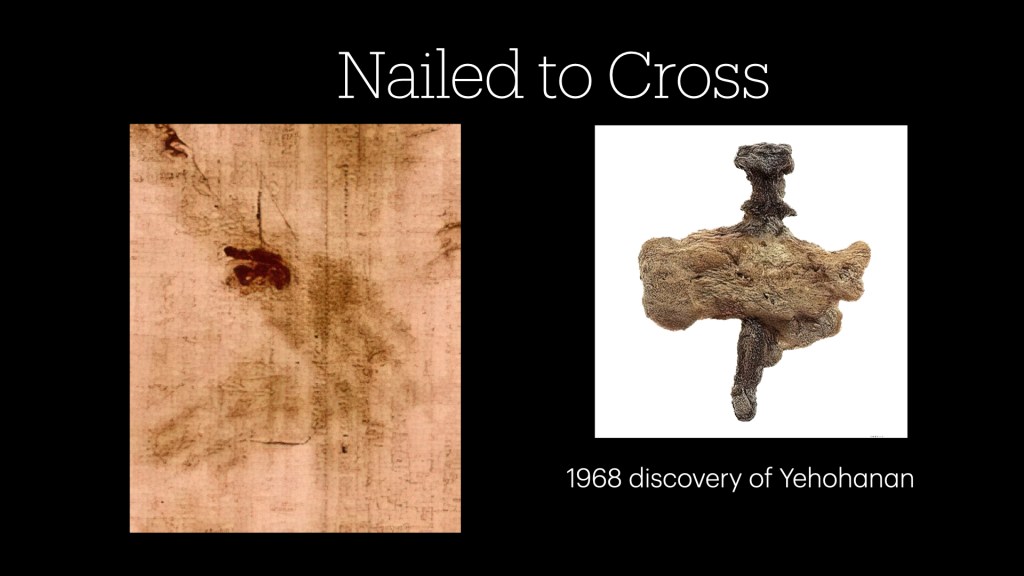

One of the most striking details on the Shroud is this right here—the wound in the wrist, not the palm. Medieval art almost always showed Jesus nailed through the palms. But here’s the thing: nails driven through the palms won’t hold a man’s weight on a cross. The tissue would tear.

Dr. Pierre Barbet, a French surgeon and author of A Doctor at Calvary, studied this in depth. He found that the nails had to be driven through the wrist, right between the small bones, in an area known as the space of Destot. That’s the only way the body could be supported without tearing free. And that’s exactly what we see on the Shroud—long before this was understood medically.

Now look at the feet. You can see exit wounds consistent with crucifixion—one foot placed over the other, with a single nail driven through both and exiting at the heel.

What we’re seeing here isn’t artistic symbolism. It’s consistent with Roman crucifixion practice. It’s forensic. The level of anatomical precision in this image—remember, an image with no paint and no brush—ought to make us stop and think.

As we move from the hands and feet, there’s another detail on the Shroud that grabs your attention immediately. One of the most dramatic features is this large elliptical wound on the right side, right between the fifth and sixth ribs.

It’s exactly where a Roman soldier would have thrust a spear to confirm death. John’s Gospel records it: ‘One of the soldiers pierced His side with a spear, and immediately blood and water flowed out’ (John 19:34).

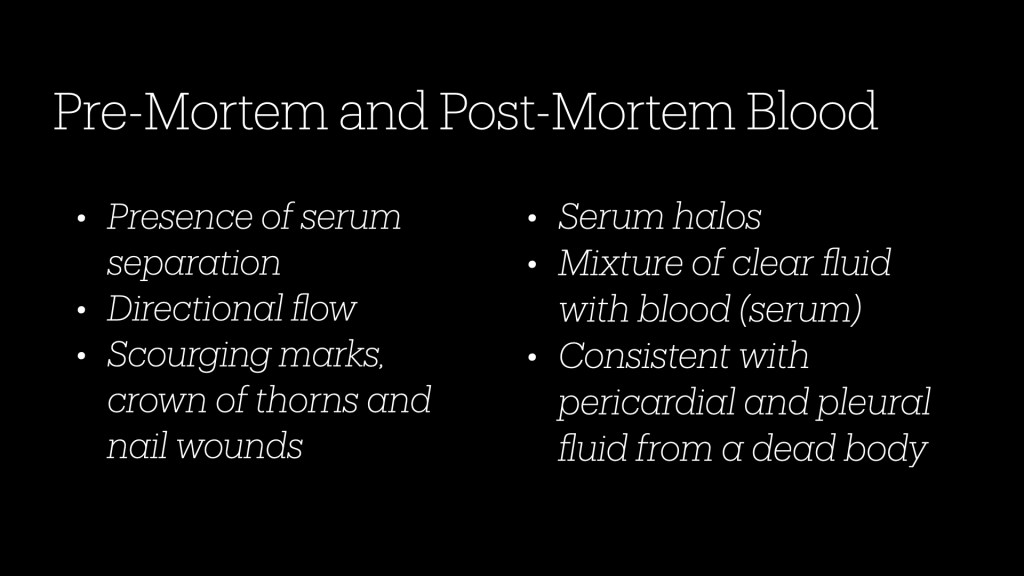

Forensic pathologists examining the Shroud have noted something fascinating here—a separation of blood and a clear, watery fluid in this area. This is exactly what you’d expect if someone had died of asphyxiation or heart failure. The fluid is consistent with what we now know as pericardial or pleural effusion. It tells us Jesus was already dead when He was pierced.

Look at the shape of the wound. It’s wide and elliptical, matching the blade of a Roman lancea. And notice how the blood flows downward—following gravity and natural post-mortem movement. Once again, what we’re seeing here is forensic and historical accuracy that would have been completely unknown to a forger centuries ago.

As we shift our focus upward, the Shroud reveals another sobering detail—the crown of thorns. But notice carefully: this isn’t the neat, wreath-like crown we see in most Christian art. The blood patterns suggest something far more brutal—a cap of thorns covering the entire scalp.

The puncture wounds are visible all across the head—front, top, and back—with blood trailing down the forehead and seeping through the hair. This isn’t artistic symbolism. It’s consistent with the way Roman soldiers would have mocked Jesus. They likely twisted thorn branches into a cap that pressed thorns deep into the skin, causing maximum pain and humiliation.

And again, the precision of what we see here is remarkable. The placement of the wounds, the angles, and the way the blood flows—all align perfectly with real scalp injuries.

Isaiah’s words come to mind here: ‘He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to Him… He was despised and rejected’(Isaiah 53). This isn’t just a crown of thorns. It’s a crown of suffering—a crown of mockery that Rome placed on the King of kings.

Now let’s bring all of this together in three dimensions. What you’re looking at is a sculpture by Spanish artist Álvaro Blanco, displayed at the Cathedral of Salamanca in Spain. This wasn’t created on a whim. It’s the result of more than 15 years of forensic research on the Shroud.

This isn’t art in the traditional sense. There’s no creative license here. Every detail—every bruise, every wound—was reconstructed from medical and anatomical analysis of the image on the cloth.

Notice the cap of thorns fully modeled. It’s not a neat circular crown, but a full covering that presses thorns into every part of the scalp, just as the blood flows on the Shroud suggest. This wasn’t simply a crown of mockery; it was a parody of kingship—a Roman insult directed at a so-called ‘King of the Jews.’

Look at the body itself. Emaciated. Bruised. Torn open by scourging. Nail wounds in the wrists and feet. A gaping side wound. This sculpture allows us to see what the Shroud has preserved—not just an image, but a forensic testimony. It’s sobering. It’s haunting. And it’s profoundly real.

Now take a look at this. Here we see the sculpture overlaid with the Shroud itself—and the match is remarkable. This isn’t a rough artistic interpretation. It’s a meticulous reconstruction, built from the actual dimensions of the man on the Shroud and aligned with every visible wound pattern.

From the position of the shoulders and arms to the precise placement of wounds on the head, back, wrists, and feet—every detail corresponds. There’s no artistic guesswork here. No halo. No idealized beauty like you’d see in traditional Christian art. What we’re looking at is the raw, anatomical reality of a man who suffered exactly as described in the Gospels.

And that alone should give us pause. Could anyone in the Middle Ages have produced this level of precision from an image they couldn’t even fully see until it was photographed centuries later?

Before we dive deeper, let’s set the stage for what comes next. In the slides ahead, we’re going to look at six key burial details found on the Shroud—each one aligning with first-century Jewish customs and with what the Gospels describe.

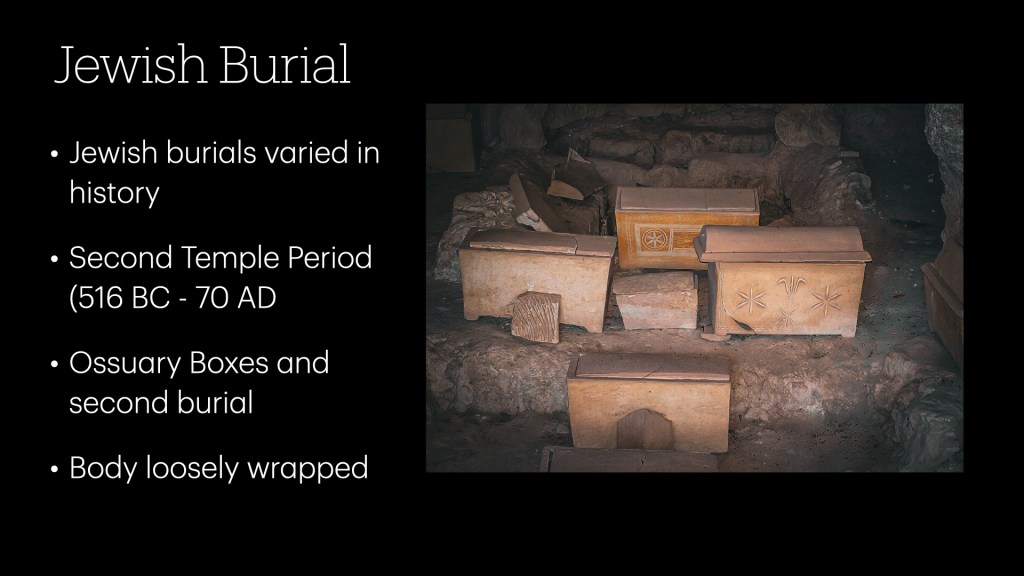

Remember, Jewish burial practices varied throughout history. But during the Second Temple period—from 516 BC to 70 AD—there were specific customs, including the use of ossuary boxes for secondary burial and the practice of wrapping the body loosely in linen.

We’re going to see how each of these six details lines up not only with Jewish burial law but also with the biblical account of Jesus’ burial. And when we lay them side by side, the parallels are striking.

Let’s begin with a quick overview of Jewish burial customs. These weren’t static—they evolved over centuries. But during the Second Temple period, roughly 516 BC to 70 AD, one practice in particular stands out: secondary burial.

Here’s how it worked. A body would first be laid in a tomb and left to decompose naturally. Later, after the flesh had decayed, the bones would be carefully gathered and placed into ossuary boxes—stone chests like the ones you see here. Archaeologists have found many of these in places like the Kidron Valley and Talpiot.

This practice also explains why bodies were loosely wrapped in linen. Unlike Egyptian mummification, there was no need for tight bindings or embalming. The wrappings weren’t meant to last forever—they were simply to honor the body until decomposition was complete.

Now, bring that back to the Shroud. What we see is a single cloth, laid under and over the body—not wrapped around in multiple layers. No tight bindings. No mummification. Everything about it—the style, the handling, the timeline—fits seamlessly within these first-century Jewish burial customs.

Here’s another detail that often surprises people: the man on the Shroud is clearly nude. In Jewish culture, this would have been considered deeply shameful—and yet that’s exactly what we see.

But think about the Gospel accounts. They tell us the Roman soldiers divided Jesus’ garments among themselves. Crucifixion wasn’t just about execution—it was meant to humiliate. Victims were often stripped naked as part of that public shaming.

Now ask yourself: if a medieval forger created this image, wouldn’t they have added a loincloth? Especially in a Christian culture where nudity was considered offensive? Instead, we find historical reality.

Notice how the hands are crossed. This isn’t artistic stylization—it’s practical. The burial party likely placed the hands this way to cover the groin as quickly as possible, out of reverence and modesty. Once again, what we see on the Shroud aligns with first-century burial practices and fits seamlessly with the Gospel narrative.

Now let’s talk about the face and hair—two details that often go unnoticed but are hugely significant. The man on the Shroud has a distinctly Semitic facial structure. Look at the prominent nose, high cheekbones, deep-set eyes, and strong jawline. Add to that a full beard and long hair, and you have features consistent with Jewish men of the first century.

This is important because most medieval European depictions of Jesus reflect their own culture—fair skin, delicate features, sometimes even light hair. But the Shroud doesn’t fit that pattern at all. Instead, it gives us something far more historically and ethnically accurate.

We see the same traits in first-century Jewish ossuary remains, on coins like the Bar Kokhba silver tetradrachm, and even in early Christian icons that predate medieval stylization.

The hair is especially intriguing. It’s long and falls to the shoulders, even tied back in what some have suggested is a Nazirite-style knot—a detail that aligns with Jewish custom and again is unlikely to come from a medieval imagination. Once more, what we see here fits perfectly within a first-century Jewish context, not a European one.

Now let’s talk about the blood—the evidence that takes this beyond art or legend. The blood on the Shroud isn’t paint, dye, or pigment. Scientific testing has confirmed it’s real human blood. And even more fascinating—it’s blood type AB.

AB is one of the rarest blood types in the world, found in less than 4% of the global population. But among Middle Eastern Jewish males, it’s significantly more common. That means the blood on the Shroud is not only human—it’s ethnically consistent with what we would expect from a first-century Jewish man.

And there’s something else. The Sudarium of Oviedo—a cloth believed to have covered Jesus’ face—and the Veil of Manoppello both show the same blood type: AB. Think about that. Three separate cloths, tied historically to the same event, all sharing the same rare blood type. This isn’t a medieval coincidence. This is biological consistency across relics connected to one crucified man.

Now let’s turn to another mysterious relic from early Christian tradition—the Mandylion of Edessa, sometimes called the Image of Edessa.

This was believed to be an image of Christ not made by human hands—a miraculous imprint of His face. Early Church historians, like Eusebius, wrote about a face cloth bearing Jesus’ image as early as the 4th century. The tradition says it was hidden within the walls of Edessa (modern Şanlıurfa, Turkey) to protect it during times of persecution.

In the 6th century, the cloth was reportedly rediscovered and became one of the most venerated Christian relics in the East. Later, in 944, it was transferred to Constantinople. But after the Crusader sack of 1204, it disappeared from historical record.

Some researchers, like Ian Wilson, propose that the Mandylion may have actually been the Shroud of Turin—folded in such a way that only the face was visible. The facial dimensions, stain patterns, and early descriptions lend surprising weight to this theory, making it a possibility worth serious consideration.

These images helps visualize a fascinating theory. Here you see how the Shroud could have been folded into eight sections, with only the face displayed. Early accounts of the Mandylion describe it as a portrait—a face only—not a full-body image.

If the Shroud was carefully folded like this and mounted in a frame, the result would have looked exactly like what ancient sources report.

What’s even more interesting is that there are visible fold lines on the Shroud today that align with this configuration. This suggests it may have been displayed this way for centuries.

If this theory holds, then the Mandylion wasn’t a different relic at all—it was actually the Shroud of Turin in disguise, hidden in plain sight under the reverence and traditions of the Eastern Church.

By 1578, the Shroud had found its way to its current home in Turin, Italy, where it remains today in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist.

A pivotal moment came in 1898 when Italian photographer Secondo Pia took the very first photograph of the Shroud. As he developed the plate in his darkroom, he made a stunning discovery: the Shroud image behaves like a photographic negative. When reversed, it revealed an astonishingly lifelike face—details that were nearly invisible to the naked eye.

This discovery ignited over a century of intense scientific study. Experts from fields as diverse as physics, forensics, textile analysis, and botany have all examined the cloth.

And despite surviving fires, water damage, wars, and waves of skepticism, the Shroud continues to draw both pilgrims and scientists. It has become more than a relic—it is now one of the most studied and controversial artifacts in all of human history.

This is the actual photograph taken by Secondo Pia in 1898—the moment that changed everything. For the first time in history, the faint, almost ghostly image on the Shroud became clear and lifelike when viewed as a photographic negative.

On the negative plate, details suddenly emerged—facial features, body proportions, wound patterns—all far more vivid than what’s visible to the naked eye on the cloth itself.

The world was stunned. A relic that had long been regarded as little more than a faded curiosity was now something profoundly mysterious.

And here’s the critical question: how could a forger in the Middle Ages have created a perfect photographic negative centuries before photography even existed? This isn’t artistry. It’s a phenomenon we still can’t fully explain.

In 1978, the Shroud entered a new chapter of scientific scrutiny. A team of over 30 scientists from various disciplines came together to form the Shroud of Turin Research Project—better known as STURP.

For five intense days, they were given unprecedented access to the cloth. They ran tests in physics, chemistry, biology, and advanced image analysis—determined to solve the mystery once and for all.

Their mission? To figure out how the image was formed and to determine whether it was the work of an artist, a natural process, or something else entirely.

After exhaustive testing, STURP issued their report in 1981. Their conclusion? ‘The Shroud image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist… The image remains an ongoing mystery.’

And that mystery persists. To this day, no one has been able to replicate the Shroud’s image using medieval materials or methods. The cloth continues to defy explanation.

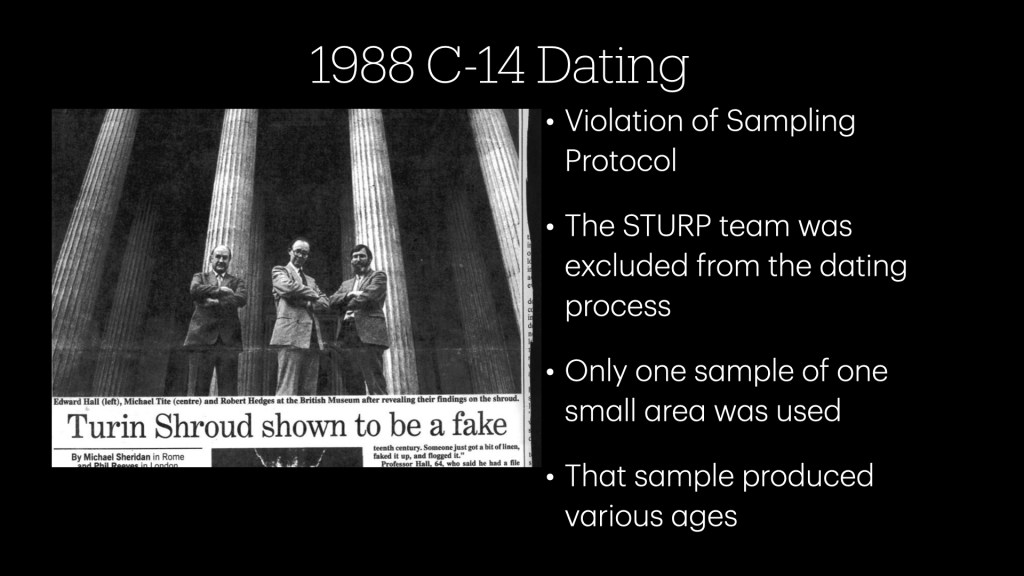

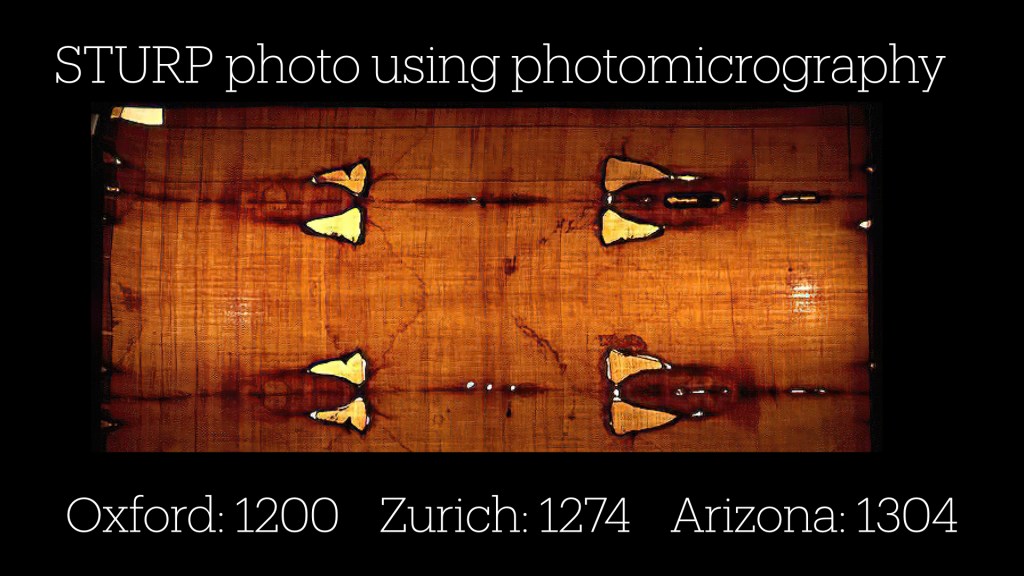

In 1988, three labs — Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona — conducted radiocarbon dating on a single sample cut from the Shroud’s corner. The results dated it between 1260 and 1390 AD, leading many to dismiss it as a medieval forgery.

But here’s the problem. That corner was later found to contain cotton interwoven with linen — likely from a medieval repair. The STURP team wasn’t involved in the process, and only one site on the cloth was tested, violating the original sampling protocol, which required multiple areas.

Photomicrography reveals that this corner is visually and chemically different from the rest of the cloth. You can see newer fibers, possible dye, and patchwork blending — evidence that this sample may not reflect the original linen.

Even the three labs returned slightly different results: Oxford dated their sample to 1200, Zurich to 1274, and Arizona to 1304. That 100-year spread hints at contamination or variation in the tested fibers.

This means the 1988 date cannot be taken as definitive. Later studies — including chemical analysis, textile studies, and historical evidence — point instead toward a first-century origin.

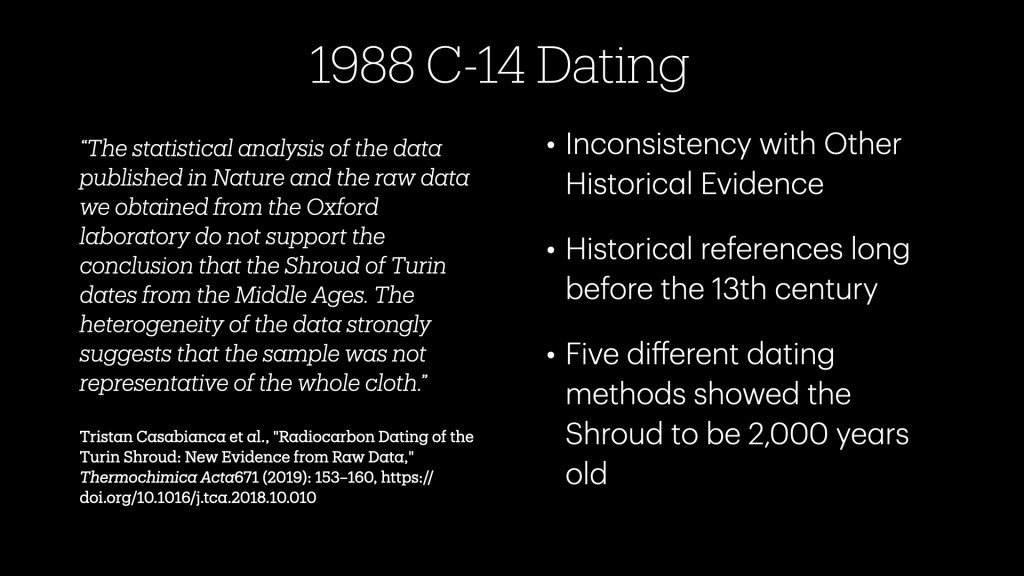

French researcher Tristan Casabianca led the team that gained access to the original raw data from the 1988 carbon dating tests. In 2019, after analyzing that data, he wrote these striking words: “The evidence for the medieval age of the Shroud of Turin is clearly not definitive… all the data must be re-examined.” This was a bold statement because for decades, skeptics had treated the 1988 results as conclusive. But Casabianca’s team discovered major statistical flaws and anomalies in the original datasets, raising serious doubts about whether the tested corner was even representative of the entire cloth.

The first key issue with the 1988 results is their inconsistency with other historical and scientific evidence. The Shroud contains pollen grains from plants found only in the Judean desert and Anatolia—regions the cloth would have needed to traverse centuries before the Middle Ages. Likewise, forensic studies have shown that the blood stains, scourge marks, and anatomical accuracy are far beyond the knowledge or capabilities of medieval artists. Simply put, the carbon dating contradicts too much other evidence to stand alone.

Second, historical references to a burial cloth bearing the image of Christ appear centuries before the 1200s. The Shroud of Constantinople, described in Byzantine records, bears striking similarities to the Turin Shroud—most notably in size, linen weave, and the faint, mysterious image. Earlier still, the Mandylion of Edessa was revered as a cloth imprinted with Christ’s face. These references suggest an unbroken chain of custody stretching far earlier than the medieval period.

Third, at least five other dating methods now challenge the 1988 conclusions. Vanillin tests on the Shroud’s linen fibers indicate a much greater age because vanillin decays over centuries and should still be present if the cloth were medieval. Textile analysis comparing the Shroud’s weave and thread type aligns it with first-century Jewish burial cloths. Mechanical and chemical testing of linen fibers has placed the Shroud closer to 2,000 years old. Even studies of environmental factors, like long-term heat exposure, suggest a timeline consistent with the era of Christ.

So rather than closing the case, the 1988 carbon dating has actually opened the door to deeper investigation. Today, scientists across multiple disciplines are questioning how such an ancient relic could carry so much forensic, botanical, and historical evidence consistent with the first century—while a small corner repair introduced a misleading date. This controversy isn’t proof of forgery; it’s a call to re-examine the data in light of everything else we now know.

Below are several peer-reviewed papers showing a 2,000 year old date for the Shroud and refute the 1988 C-14 dating.

This slide comes directly from my paper Sacred Threads: The Shroud of Turin in Scriptural and Jewish Context, where I compiled the results of multiple scientific dating methods applied to the Shroud. It visually compares five independent tests—Raman spectroscopy, FTIR, vanillin content, tensile strength, and WAXS—each placing the Shroud’s origin well within the first century, overlapping the timeframe of Christ’s crucifixion. In stark contrast, the 1988 C-14 test appears as an outlier, isolated in the medieval period. This chart underscores the growing scientific consensus that the Shroud’s true age may align far more closely with the historical Jesus than with any medieval forgery theory.

This slide brings everything together by showing why the Shroud’s evidence must be weighed cumulatively, not in isolation. Each individual piece—whether forensic, historical, textile, botanical, or chemical—points in the same direction, but when combined, they form an overwhelming case for authenticity. Bayesian probability provides a framework for this cumulative assessment. It’s a tool widely used in science and law to update the odds as new evidence is added. In Sacred Threads, I go into greater detail on this analysis, showing how even with just five lines of evidence, the odds of forgery shrink to 1 in over 15 million. When all thirty factors from the paper are considered, the cumulative likelihood ratio yields a posterior probability of 99.998%. At that level, the question shifts from “Why believe?” to “Why doubt?”—because this isn’t about blind faith, but a rational response to the converging weight of evidence.

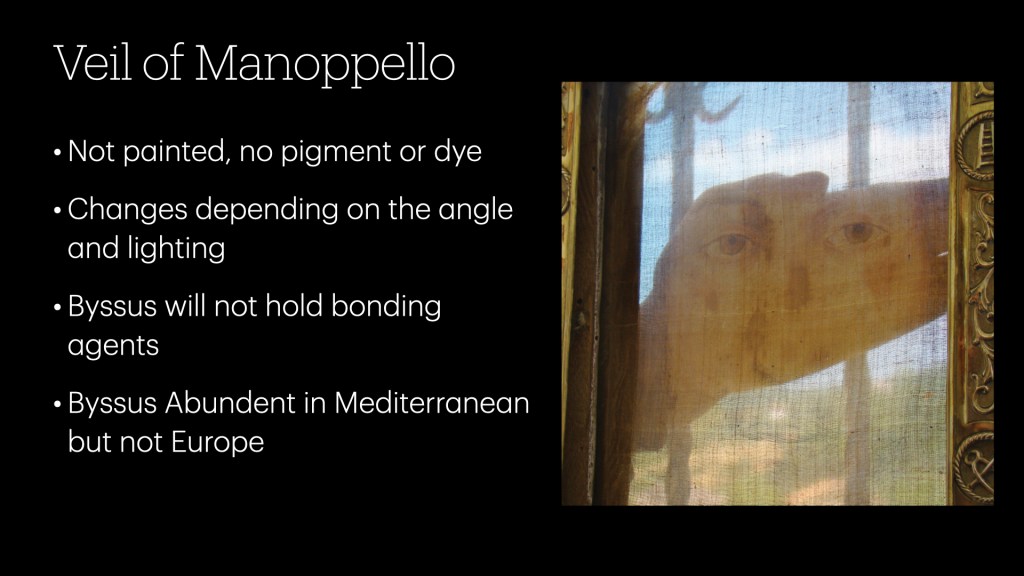

This slide introduces the Veil of Manoppello, a relic shrouded in mystery that displays what many believe to be the living face of Christ. Unlike the Shroud of Turin, where the eyes are closed in death, the Veil shows Christ with His eyes open and mouth slightly parted—as if taking His first breath after resurrection. The material itself adds to the intrigue; it is made of byssus, or sea silk, a rare and incredibly delicate fiber that scientists confirm is impossible to paint on without damaging. Some traditions identify this as the “Veronica” cloth—the true image of Christ given to Veronica on the way to the cross—while others suggest it captures the very moment of resurrection. Whether a miraculous image or a sacred mystery, the Veil challenges us to imagine what the disciples saw when they first encountered the risen Jesus.

This slide highlights the extraordinary and puzzling nature of the Veil of Manoppello. Microscopic studies have revealed no trace of pigment, dye, or bonding agents on the fibers—meaning the image was not painted, printed, or applied in any conventional way. Even more astonishing, the image seems to shift depending on lighting and viewing angle—sometimes fading into near invisibility, other times appearing almost three-dimensional. This phenomenon is partly due to its composition: the veil is made of byssus, or sea silk, an ancient Mediterranean fabric so delicate it cannot hold paint or ink. While byssus was prized in antiquity, it was virtually unknown in medieval Europe, making it even harder to explain how a supposed medieval forger could have accessed the material and produced such an image without damaging it.

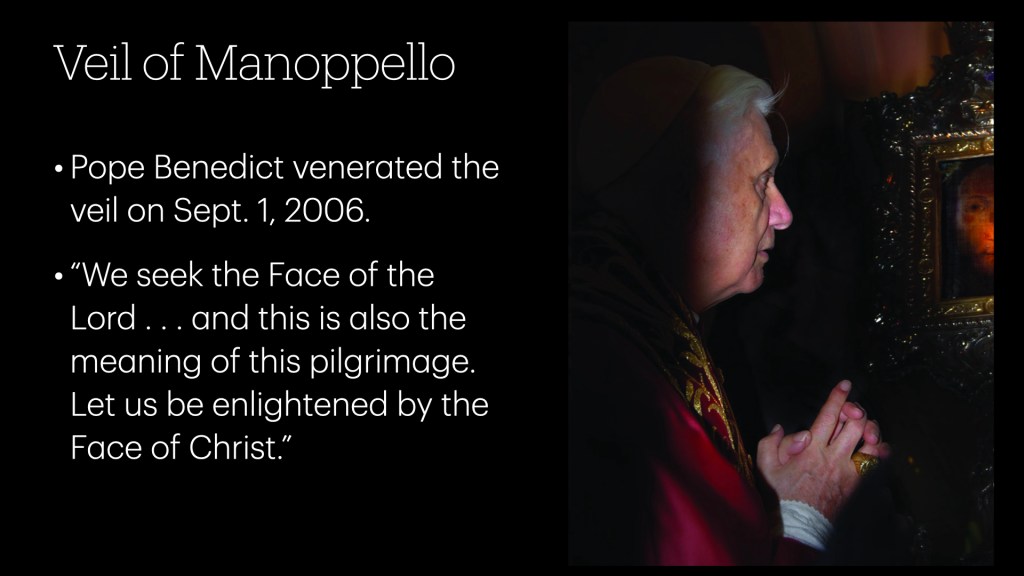

In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI made a historic pilgrimage to Manoppello to venerate the Veil. Standing in prayer before the image, he reflected, “We seek the Face of the Lord… and this is also the meaning of this pilgrimage. Let us be enlightened by the Face of Christ.” His words capture the profound spiritual impact this mysterious cloth continues to have, drawing people from all traditions to contemplate the possibility of gazing upon the human face of God.

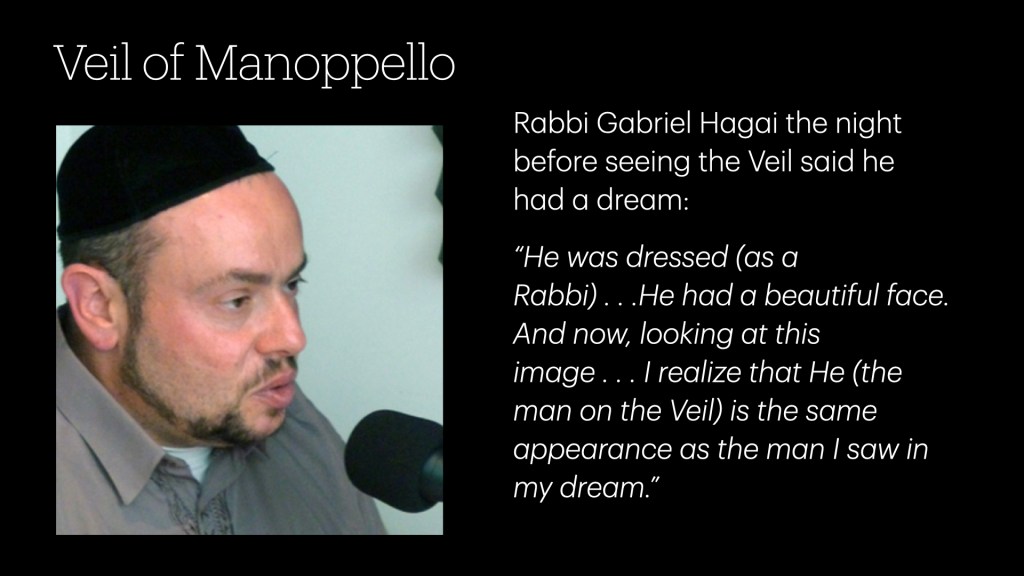

What’s equally remarkable is the story of Rabbi Gabriel Hagai. The night before his first encounter with the Veil, he had a vivid dream in which a man dressed as a rabbi came to him and spoke, identifying Himself as Jesus. Rabbi Hagai described the man as having “a beautiful face” that deeply moved him. The next day, when he saw the Veil for the first time, he was startled to recognize the same face from his dream. “This is the same appearance as the man I saw in my dream,” he said. To him, the image bore the unmistakable features of a first-century Jewish man — not the product of medieval European imagination, but something authentic and deeply Semitic.

These two testimonies — one from a pope, the other from a Jewish rabbi — illustrate the unique, lifelike quality of the Veil and its ability to transcend religious and cultural boundaries, inviting all who see it to wrestle with its origin and meaning. (You can listen to Rabbi Hagai’s own account at the above YouTube link.)

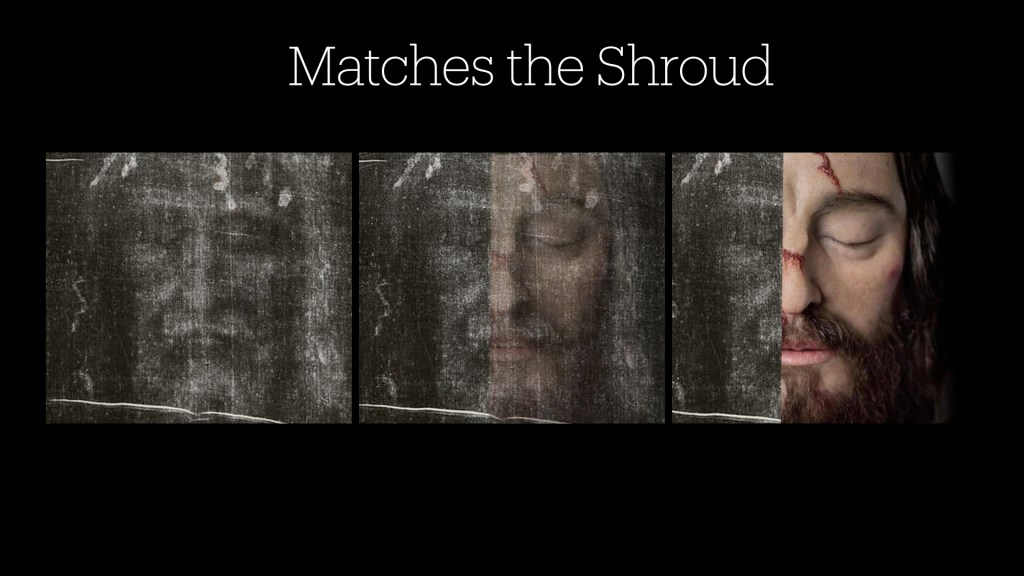

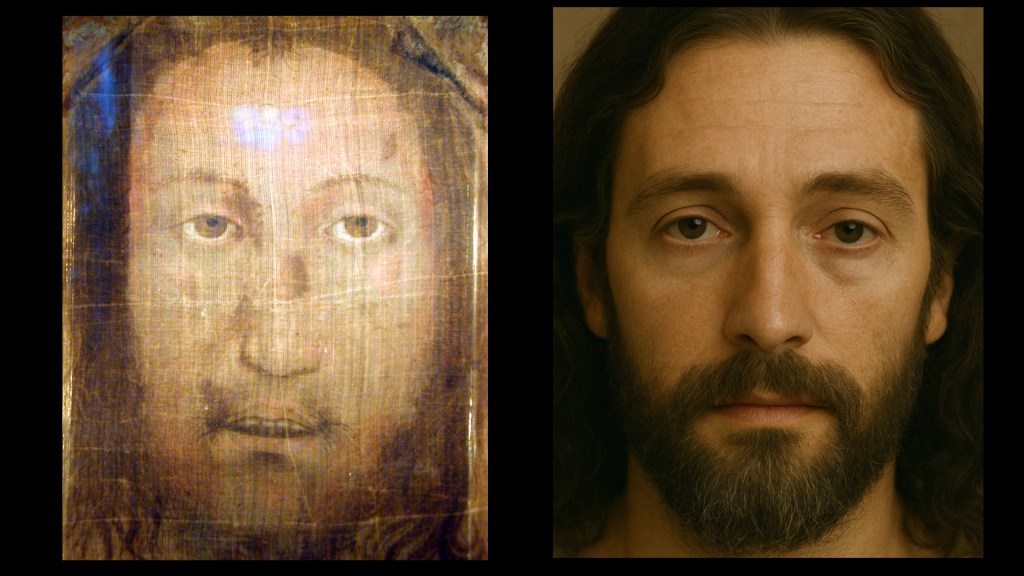

These final slides bring us to a stunning visual comparison between the Shroud of Turin and the Veil of Manoppello. Placing their faces side by side reveals remarkable similarities: both depict a man with long hair, parted beard, and pronounced Semitic features. Yet they are not identical — the Shroud shows the face of a man beaten, lifeless, and marked by suffering, while the Veil reveals a face that appears whole, serene, and alive.

To explore this further, AI composites were created separately from each image. The resulting reconstructions highlight the continuity between the two — subtle differences, but striking harmony. Displaying the two AI-generated faces next to each other evokes a sense of transformation: one image speaks of death and sacrifice; the other hints at life and resurrection. This raises a profound question: are these two relics snapshots of the same man, captured in two defining moments — burial and victory over death?

This slide brings all four faces together: the original images from the Shroud and the Veil, alongside their respective AI-generated reconstructions. Using advanced facial recognition and forensic software — the same kind employed by the FBI and law enforcement agencies — the comparison revealed a stunning 90–95% alignment between them. To put that into perspective, U.S. law enforcement will often act on an 80% match, and in court, a 90% facial alignment is considered admissible evidence. While I’m not claiming these AI composites represent the exact face of Jesus, it’s remarkable that two ancient cloths, crafted from different materials and preserved in separate locations for centuries, align so closely when analyzed with modern technology.

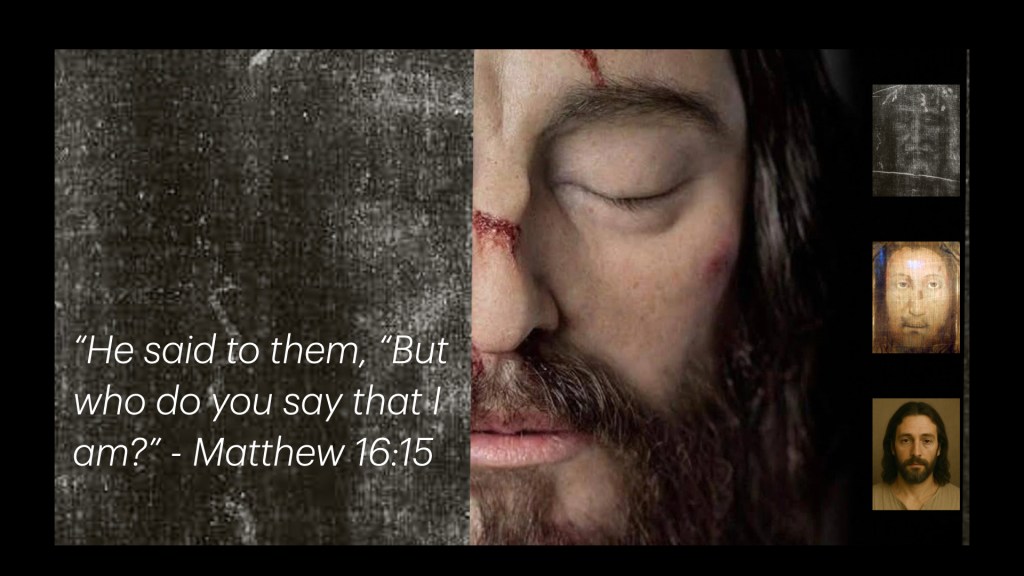

This image offers only a hypothesis — a visual way to imagine how both cloths could be true. Here we see the Shroud and the Veil together: one showing the body of a crucified man wrapped for burial, the other perhaps revealing the moment of return to life. Could this represent two moments in time? The Shroud bearing witness to His suffering and burial, and the Veil showing His life and resurrection?

We cannot claim this with absolute certainty. But as with much of this journey, it remains a mystery — and yet a mystery supported by astonishing evidence.

Perhaps God has left these cloths as quiet witnesses, not to compel belief, but to invite us to reflect more deeply. As Jesus Himself asked: “Who do you say that I am?”

That’s the question these images seem to whisper across centuries — and the one each of us must answer.

Leave a comment