A Multi-Disciplinary Response to Cicero Moraes

It’s not every day that an ancient piece of cloth inspires passionate debate across scientific, historical, and theological domains. The Shroud of Turin—believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth—remains one such artifact. Recently, 3D forensic modeler Cicero Moraes offered a theory suggesting that the Shroud’s image could have been formed by a bas-relief or similar artistic method. His approach, while visually creative and technically polished, falls short under close multidisciplinary scrutiny. This post offers a distinct response to Moraes’s claims, building on scientific, historical, and theological insights not commonly explored in rebuttals.

This blog is best read in tandem with my full-length research paper, Sacred Threads: The Shroud of Turin in Scriptural and Jewish Context, which explores the Shroud’s alignment with first-century Jewish burial customs, historical testimony, and theological implications. You can access the full paper here:

https://tomstheology.blog/sacredthreads

What Moraes Proposes

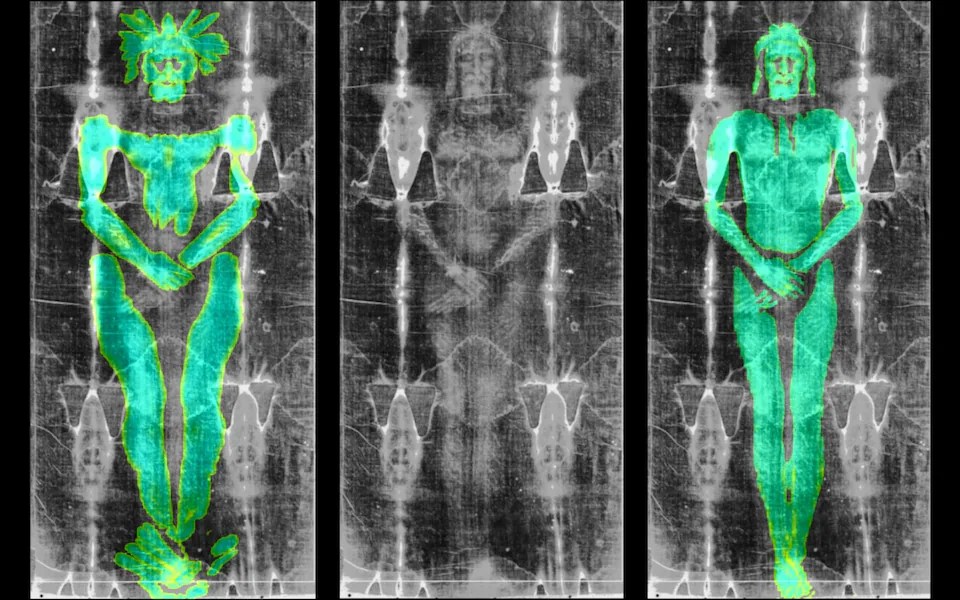

Moraes, known for facial reconstructions using forensic 3D modeling, applies his expertise to suggest that the Shroud image could have been produced via a bas-relief or similar physical object pressed into contact with cloth. He argues that variations in image intensity correspond with relief depth, implying an artistically engineered result. Even if a digitally draped image resembles the Shroud visually, it does not replicate the chemical, microscopic, or physical properties confirmed by direct testing.

While Moraes claims his method accounts for the image’s anatomical realism and general proportions, this theory commits a fundamental flaw: it presumes that physical contact explains the Shroud’s image without adequately accounting for multiple properties of the image that physical contact alone cannot replicate.

1. Spatial Encoding: A Property No Artist Could Have Predicted

Perhaps the most baffling feature of the Shroud image is its three-dimensional spatial encoding. The image intensity correlates directly with cloth-body distance—not pressure, not ink density, not pigment layering. This was first revealed through analysis with the VP-8 Image Analyzer in 1976. Unlike typical photographs or paintings, which distort when subjected to 3D mapping, the Shroud’s image produced a coherent 3D relief.

No other known ancient image demonstrates this property. Not the Mona Lisa. Not the Fayum portraits. And certainly not any medieval bas-relief artifact. If this were an artist’s invention, it would be a feat of engineering far ahead of its time—yet without precedent or replication.¹

2. Top-Down Image Formation: Superficial Yet Precise

Under microscopic analysis, the image resides only on the outermost 1–2 microns of the linen fibrils—less than the thickness of a red blood cell (about 200 nanometers deep). There is no evidence of capillary action or ink penetration. In fact, the image does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light, unlike known burns or scorches.²

Even more remarkable, the image was not formed by any pigments, paints, dyes, or binders. STURP (the Shroud of Turin Research Project) confirmed this through X-ray fluorescence, infrared spectroscopy, and microchemical testing.³ A contact image like Moraes’s model would almost certainly leave behind more than just surface discoloration—it would involve deformation, capillary wicking, and distortion.

None of that is present.

3. The Draping Problem: Undistorted Yet Impossible

One of the most overlooked difficulties for contact theories like Moraes’s is the issue of cloth draping. When a fabric is laid over a three-dimensional form—like a human face or torso—it conforms to topography, creating distortion. Yet the Shroud image is not distorted. Dr. John Jackson’s cloth-draping experiments, conducted using life-sized manikins and laser-mapped topography, revealed that a contact model would produce severe horizontal distortions, especially around the cheeks, sides of the face, and body flanks.⁴

Moraes’s model does not address this. He simply assumes contact transfer without distortion, despite this being a physical impossibility.

4. The Blood Is Not the Image

In Moraes’s renderings, it appears that the image and bloodstains emerge as part of the same modeling exercise. This assumption ignores a fundamental detail: the blood is not part of the image. The bloodstains on the Shroud are anatomically accurate, distinguishable under spectroscopy, and precede the image.⁵

Furthermore, the blood itself is consistent with human, complete with bile pigments and serum separation.⁶ High-resolution UV fluorescence photography revealed serum halos consistent with postmortem clotting—a phenomenon an artist in the 13th century could not have anticipated, let alone replicated.

5. Medical Forensics: The Signature of Death

The man of the Shroud shows evidence of rigor mortis, postmortem blood flow, and anatomical consistency with Roman crucifixion practices—such as injuries to the wrist (not palms), scourge marks consistent with a Roman flagrum, and separated shoulder joints. These forensic details were confirmed by multiple pathologists, including Pierre Barbet and Dr. Robert Bucklin.⁷

A static bas-relief would be hard-pressed to incorporate such dynamic physiological details—especially those visible only to modern forensic science.

6. Historical Inconsistency: The “Mask of Agamemnon” Error

Moraes likens the Shroud to the Mask of Agamemnon, discovered in Mycenae. But this analogy is flawed. The mask is a hammered gold funerary covering—not a contact image, not a cloth-based medium, and not comparable in its material or formation process. It is akin to comparing a fingerprint to a coin impression: both have contours, but their origins and features are categorically different.

Additionally, no artistic tradition—Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, or otherwise—shows any precedent for the unique properties of the Shroud. There is no evolutionary trail, no lesser prototypes, and no workshop records for such a technique.

7. Dating and the WAXS Revolution

Moraes leans on the 1988 radiocarbon dating that placed the Shroud in the medieval period. However, subsequent textile studies (including those using Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering, or WAXS) have called this conclusion into serious question. Dr. Tristan Casabianca and others have published peer-reviewed analyses showing that the original 1988 samples were likely taken from a repaired section of the cloth.⁸

Dr. Liberato De Caro’s 2022 WAXS study dated Shroud fibers to the 1st century with 95% confidence.⁹ These results are not alone. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy studies also indicate ancient linen aging consistent with a 1st-century origin.

8. Image Replication Experiments: Every Attempt Falls Short

Countless scientists and artists have attempted to replicate the Shroud using radiation, heat, pigments, or chemical reactions. None have succeeded in reproducing all the known properties:

- Superficiality to the top 1–2 microns

- No fluorescence

- No pigment or binder

- Correct 3D spatial encoding

- Anatomical realism

- No distortion from draping

- Bloodstains that predate the image

For instance, Giulio Fanti’s corona discharge models produced partial similarities, but failed to account for the blood-image separation and lacked consistency in fibril coloration. Luigi Garlaschelli’s painting attempts were visible under microscopy as having pigment residue, and failed UV tests.¹⁰

In science, replication is key. The Shroud remains an unreplicated artifact.

9. Philosophical Honesty: When the Evidence Pushes Back

Moraes is undoubtedly skilled in digital modeling. But science demands more than plausible rendering—it demands explanatory power.

When an artifact defies replication, resists simplistic categorization, and produces multiple layers of interdisciplinary anomaly, the burden is not on defenders of authenticity to explain everything with finality. Rather, the burden shifts to the skeptic to produce a model that explains all the data better. Moraes’s model does not come close.

One may rightly remain agnostic about the Shroud’s full origin. But if one is to speak honestly, scientifically, and historically, then Moraes’s bas-relief theory fails the test of coherence, completeness, and explanatory rigor.

As John 1:14 says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” If the Shroud is what it appears to be, then it is not only an object of curiosity—but a signpost pointing toward that Incarnation.

Conclusion

Moraes’s paper may impress with its digital artistry, but it fails to grapple with the depth of the data.

This is simply an already disproven hypothesis dressed in new digital clothing. It recycles contact-based theories that have long been shown inadequate—and gives them a fresh look without fresh substance. The headlines may be new, but the assumptions are not. And unfortunately, this is where the media leads, not where the science does.

Decades of research—especially from the STURP team—have already demonstrated that the image on the Shroud is not the result of painting, burning, scorching, or any known artistic method. As STURP concluded in 1981:

“The image is not the result of any known mechanism—be it rubbing, painting, scorching, or vapor contact.”

—STURP Final Report

A valid theory of the Shroud must explain not just what we see,

but how we see it—and how it got there.

The Shroud is not just mysterious. It’s measurable. And the more we measure,

the more it pushes back against every naturalistic explanation.

Footnotes

¹ John P. Jackson, Eric J. Jumper, and William R. Ercoline, “Correlation of Image Intensity on the Turin Shroud with the 3-D Structure of a Human Body Shape,” Applied Optics 23, no. 14 (1984): 2244–2270.

² Ray Rogers, “Scientific Method Applied to the Shroud of Turin,” 2003.

³ Alan D. Adler and John H. Heller, “A Chemical Investigation of the Shroud of Turin,” Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal 14, no. 3 (1981): 81–103.

⁴ John Jackson, “An Hypothesis for Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin,” 1990.

⁵ Ibid.

⁶ Alan D. Adler, “Further Spectroscopic Investigations of Samples of the Shroud of Turin,” Shroud Spectrum International 34 (1990).

⁷ Pierre Barbet, A Doctor at Calvary (New York: Image Books, 1963); Robert Bucklin, “The Shroud of Turin: A Pathologist’s Viewpoint,” Shroud Spectrum International, no. 3 (1982).

⁸ Tristan Casabianca et al., “Radiocarbon Dating the Shroud of Turin: New Evidence from Raw Data,” Thermochimica Acta 673 (2019): 1–7.

⁹ Liberato De Caro et al., “X-ray Dating of Ancient Linen,” Heritage 5, no. 2 (2022): 860–870.

¹⁰ Luigi Garlaschelli, “Life-size Reproduction of the Shroud of Turin and its Image,” Journal of Imaging Science and Technology 53, no. 6 (2009): 060501.

Leave a comment