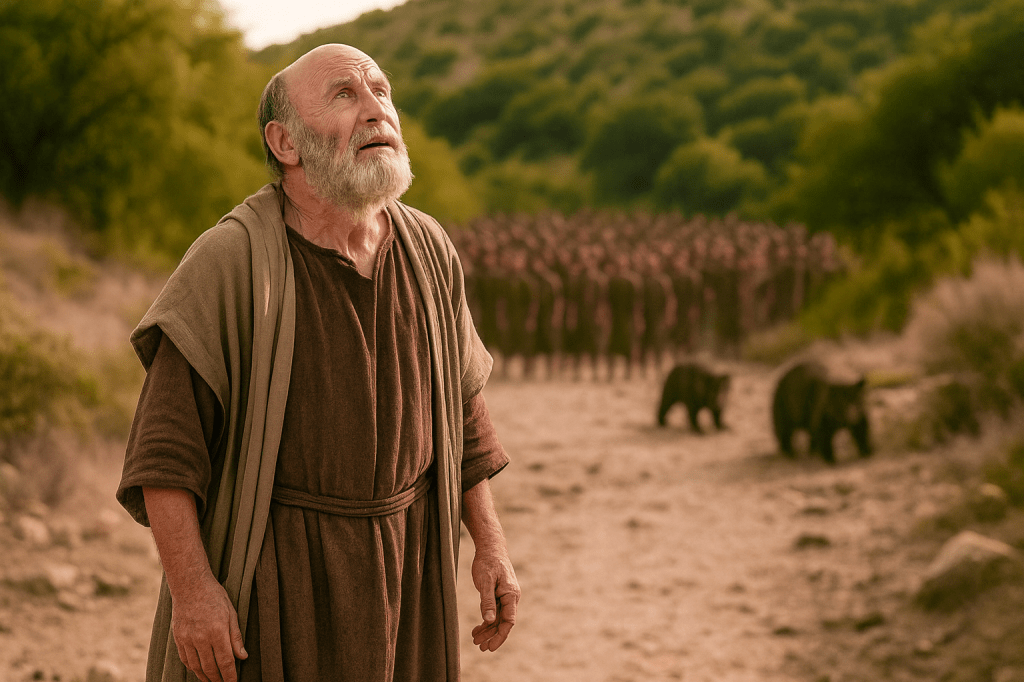

Understanding 2 Kings 2:23–25

“Then he went up from there to Bethel; and as he was going up the road, some youths came from the city and mocked him, and said to him, ‘Go up, you baldhead! Go up, you baldhead!’ So he turned around and looked at them, and pronounced a curse on them in the name of the Lord. And two female bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the youths. Then he went from there to Mount Carmel, and from there he returned to Samaria.”

– 2 Kings 2:23–25 NKJV

This passage has long troubled readers. Did God really allow two bears to kill dozens of children simply for mocking Elisha’s baldness? Critics cite this story as an example of divine cruelty, and even believers may struggle with how such an event fits within God’s justice and mercy.

But careful study shows this is not a case of petty revenge because playground children were mocking Elisha. Instead, it is a covenantal sign that demonstrates the seriousness of scorning God’s word and His messenger, especially in a culture of violence.

The Setting: Bethel’s Rebellion

Bethel, where this occured, was infamous as a center of idolatry. Jeroboam had placed one of his golden calves there (1 Kings 12:28–33), and prophets like Amos and Hosea condemned its corruption (Amos 3:14; Hosea 10:15).

For Elisha to approach Bethel was to confront a city hardened in rebellion. The hostility of the crowd reflected more than personal disdain; it revealed a community rejecting Yahweh’s authority.

Who Were the “Youths”?

The text describes the mockers as “youths,” translating the Hebrew phrase naʿarim qetannim.

- Naʿar can mean a servant or a young man, sometimes even one old enough for responsibility (Joseph at 17 is called a naʿar in Genesis 37:2).

- Qetannim can mean “small” or “insignificant,” not necessarily referring to age.

This points to a large group of hostile young men—likely late teens or older—not small children as we understand it. The fact that forty-two of them were mauled confirms it was a mob, not toddlers playing in the street.

The Insult: “Go Up, Baldhead!”

The taunt had deep meaning.

- “Go up” likely mocked Elijah’s ascension into heaven just prior (2 Kings 2:11). The crowd was deriding Elisha’s authority: “Why don’t you vanish like your master?” Or, even: “Why don’t you die and go to heaven.”

- “Baldhead” could have mocked his appearance, but baldness also carried associations of shame (Isaiah 3:24).

This was not harmless teasing but open rejection of God’s prophet. The Hebrew makes clear these were older youths — likely late teens or in their twenties — who in that culture were still technically “children” under their fathers but fully capable of organized violence. Their chant, “Go up, baldhead,” was more than playground teasing; it was a public threat against God’s prophet, effectively demanding that he die, or disappear like Elijah. In modern terms, this was closer to a street gang surrounding a pastor in a hostile city than to toddlers shouting names. God’s response was protective: just as police dogs are sometimes released to defend against attackers today, God allowed the bears to scatter and maul the violent mob to preserve His prophet’s life.

The Bears and the Forty-Two

Two female bears mauled forty-two of the youths. This detail seems severe, but it is important to note:

- The text does not say they were killed, only mauled—injured. The Hebrew word used is וַתְּבַקַּעְנָה (watĕbaqqaʿnāh), from the root בָּקַע (baqaʿ), meaning “to split, tear, or rend,” which points to the bears violently mauling the youths, but does not state that they were killed.

- The number “forty-two” recalls other moments of judgment in Israel’s history (2 Kings 10:14), signaling divine retribution.

This was not disproportionate punishment for name-calling but a sign of covenant judgment on a rebellious city.

Covenant Context

In Israel’s covenant structure, prophets were God’s authorized spokesmen. To reject them was to reject God Himself (Deuteronomy 18:19). Elisha was Elijah’s successor, newly confirmed as God’s prophet. Mocking him was symbolic of scorning Yahweh’s authority.

The mauling of the youths served as a visible warning: rebellion brings consequences. It was a dramatic sign-act of judgment, not a personal vendetta.

Theological Reflections

The story of Elisha and the bears reminds us that God takes His word and His messengers seriously. Elisha was not acting in his own authority but as God’s prophet, commissioned to speak and act in the Lord’s name. To mock Elisha was to mock the God who sent him. The incident underscores the reality that God defends His word and His servants, and that to reject them is to reject Him.

This passage also brings into focus the sobering reality of judgment. The covenant relationship between Israel and God meant that rebellion against His authority had consequences. The bears were not a random act of cruelty but a dramatic sign of covenant justice. At the same time, the severity of the judgment highlights the holiness of God, reminding us that His patience does not cancel His justice.

Finally, we see how the event fits into the broader prophetic tradition. Prophets often performed or enacted symbolic acts to demonstrate God’s truth. Here, the mauling of the youths became a visible sign of what would befall Israel if it continued in its defiance. In contrast, when we turn to the New Testament, we see Christ Himself bearing the ultimate curse on the cross so that judgment would give way to mercy. In Elisha, judgment fell on the rebels; in Christ, judgment fell on the Savior so that rebels might be redeemed.

Lessons for Today

For modern readers, this strange story carries important lessons. First, it challenges us to take God’s word seriously. In a culture that often mocks, trivializes, or openly rejects Scripture, Elisha’s story reminds us that God is not indifferent when His truth is scorned. Just as the mob at Bethel opposed the prophet, our world continues to oppose God’s authority, and the consequences of such rejection are no less real today.

The story also functions as a cultural warning. Communities and nations that mock God, like Bethel did, ultimately bring judgment upon themselves. The bears remind us that God will not be mocked indefinitely. Yet, this truth should not drive us to despair but to humility and repentance, knowing that mercy is still offered through Christ.

Most of all, the passage calls us to see the balance of justice and mercy. God’s holiness demands judgment, but His love provided a way of escape at the cross. The warning at Bethel points forward to the hope of Calvary. Just as God once defended His prophet from a hostile crowd, He continues to protect and sustain His people today, even when the world stands against them.

A Warning and a Hope

At first glance, the story of Elisha and the bears seems harsh. But when read in context (historical, contextual, and exegesis) it becomes clear: this was not about Elisha’s pride but about God’s authority. Bethel’s mockery of the prophet symbolized Israel’s rebellion, and God’s covenant judgment came swiftly as a warning.

Far from undermining faith, the passage points us to God’s holiness and justice. It also points us to the hope of the gospel: the judgment that fell outside Bethel foreshadows the judgment Christ bore at Calvary, so that mercy might come to us.

The bears remind us that God is not mocked. The cross reminds us that God is merciful. Both truths stand together.

References

- Richard D. Nelson, First and Second Kings (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2013), 165.

- Paul R. House, 1, 2 Kings (NAC; Nashville: B&H, 1995), 270.

- John H. Walton, Victor H. Matthews, and Mark W. Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 392.

- Tremper Longman III and Raymond B. Dillard, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 200.

Leave a comment