Facts That Stand Regardless of Conclusion

No matter of what one ultimately concludes about the Shroud of Turin, there are several facts about it that are simply not in serious dispute. These facts do not require belief in its authenticity as Jesus’ burial cloth, nor do they demand any particular theological commitment. They are matters of scientific observation, historical discussion, and scholarly debate. Any honest evaluation must begin here.

First, the 1988 carbon-14 dating has been widely and seriously contested. This is not a fringe claim, nor is it limited to those who already believe the Shroud is authentic. The sample was taken from a single corner of the cloth, an area later shown to contain evidence of repair and possible contamination. Subsequent peer-reviewed studies have raised substantial questions about sample representativeness, textile heterogeneity, bioplastic coatings, and statistical handling of the data. For this reason, even many skeptical researchers have acknowledged that, if possible in the future, new testing—whether radiocarbon or alternative methods—should be conducted under more rigorous and transparent conditions. This alone should caution against treating the 1988 date as a settled conclusion.

Second, the image on the Shroud is superficial in an extraordinary way. It resides only on the outermost fibers of the linen threads, without penetrating into the fibers themselves and without seeping through the cloth. This feature sharply distinguishes it from dyes, paints, scorch marks, or any known artistic technique. The coloration is the result of a subtle chemical alteration of the linen’s surface—something that remains unexplained and, crucially, has never been successfully reproduced.

Third, the image behaves as a photographic negative. When photographed and reversed, the negative becomes a positive image, revealing anatomical detail, depth, and clarity that are otherwise difficult to discern with the naked eye. This discovery, first noticed in 1898, was entirely unknown prior to the invention of photography and remains one of the most striking and perplexing characteristics of the cloth.

Fourth, when the image data from the Shroud is analyzed using three-dimensional imaging technology such as the VP-8 Image Analyzer, it produces coherent depth information proportional to body-to-cloth distance, a property not found in paintings, photographs, or conventional images and one that further distinguishes the Shroud as a unique physical anomaly.

Fifth, there is blood on the Shroud. Regardless of debates over blood type, it is not painted blood, not pigment, and not the product of artistic imagination. The bloodstains are anatomically coherent, consistent with traumatic injury, and precede the image formation itself. Even skeptical researchers have repeatedly affirmed that real blood is present on the cloth.

Finally, the Shroud remains an anomaly. It is not the product of painting, dyeing, rubbing, scorching, or any known medieval artistic process. Despite decades of experimentation, no one has been able to reproduce all of its properties—image superficiality, negative behavior, three-dimensional information, chemical characteristics, and anatomical coherence—using a single mechanism or method. Whatever the Shroud is, it is not a solved problem.

These points alone do not prove the Shroud’s authenticity. But they do establish something important: dismissal is not warranted.

I write this as an evangelical Christian myself, someone who affirms the authority of Scripture and the centrality of the Gospel. The concerns addressed here are not abstract or hypothetical. They are the three most common objections I repeatedly hear from fellow evangelicals when the Shroud of Turin is raised in conversation. What follows is not an attempt to pressure belief or elevate an artifact to the level of doctrine, but to clarify misunderstandings and to show why these objections, though understandable, do not warrant dismissing the Shroud without careful consideration.

Objection One: “The Shroud Is Just a Catholic Relic”

Among evangelicals especially, one of the most immediate reactions to the Shroud is visceral rather than analytical. It is often rejected simply because it is perceived as a “Catholic relic.” But this objection does not survive even minimal historical scrutiny.

If the Shroud can be traced back to its earlier history—often associated with Edessa and Constantinople—it was not in the custody of the Roman Catholic Church for the majority of its existence. In fact, for centuries it was associated with the Eastern Christian world and, functionally speaking, the Orthodox tradition. Even if one brackets that earlier history and begins only with the Shroud’s undisputed medieval record, it still does not primarily belong to the institutional Catholic Church. For much of its known history, it was held by private custodians, most notably the House of Savoy, a ruling family—not the papacy. Only later was it transferred to ecclesiastical care.

But even this historical clarification ultimately misses the deeper issue. Custodianship has no bearing on authenticity or significance. Artifacts are not validated or invalidated by who temporarily holds them. Archaeology does not work that way, and neither does Christian history.

Evangelicals already accept this principle in other areas. We trust the Greek New Testament manuscripts that form the basis of our modern Bibles, even though they were preserved and transmitted through both the Eastern and Western churches. We do not reject the Gospel of John because it passed through Orthodox hands, nor do we dismiss Pauline letters because Catholic monasteries preserved them. Likewise, the physical site traditionally identified as Jesus’ tomb in Jerusalem has long been under the custodianship of Orthodox and Catholic communities, yet evangelicals freely visit it and affirm its historical plausibility.

If evangelicals reject the Shroud solely because of its association with Orthodoxy or Catholicism, then the rejection is not based on evidence, but on bias and prejudice. Christianity predates denominational boundaries. Any artifact that has existed within the stream of Christian history must be evaluated on historical, textual, and scientific grounds—not sectarian discomfort.

The question is not who held the Shroud at various points in history. The question is whether it has biblical relevance and whether its features are consistent with what Scripture describes. Those are questions all Christians are entitled to explore.

It is also worth noting that even within Roman Catholicism itself, the Shroud has never been dogmatically proclaimed authentic. The Church has consistently refrained from issuing an authoritative declaration on its origin, allowing freedom of scholarly and scientific investigation. While many popes have publicly venerated the Shroud and spoken of it as a powerful aid to meditation on the suffering of Christ, veneration does not equal doctrinal endorsement. This restraint underscores an important point: engagement with the Shroud is not a matter of ecclesial obligation but of historical and evidential inquiry. Evangelicals, therefore, are not being asked to accept a Catholic doctrine, but to consider a historical artifact that even Catholics themselves are free to evaluate.

With denominational concerns set aside, the next objection often raised is not about who preserved the Shroud, but whether it actually aligns with what the Gospels describe about the burial of Jesus.

Objection Two: “It Doesn’t Match the Burial Cloths in the Gospels”

Another frequent claim is that the Shroud does not fit the burial descriptions found in the New Testament. But this objection rests almost entirely on misunderstandings of both the biblical text and first-century Jewish burial practices.

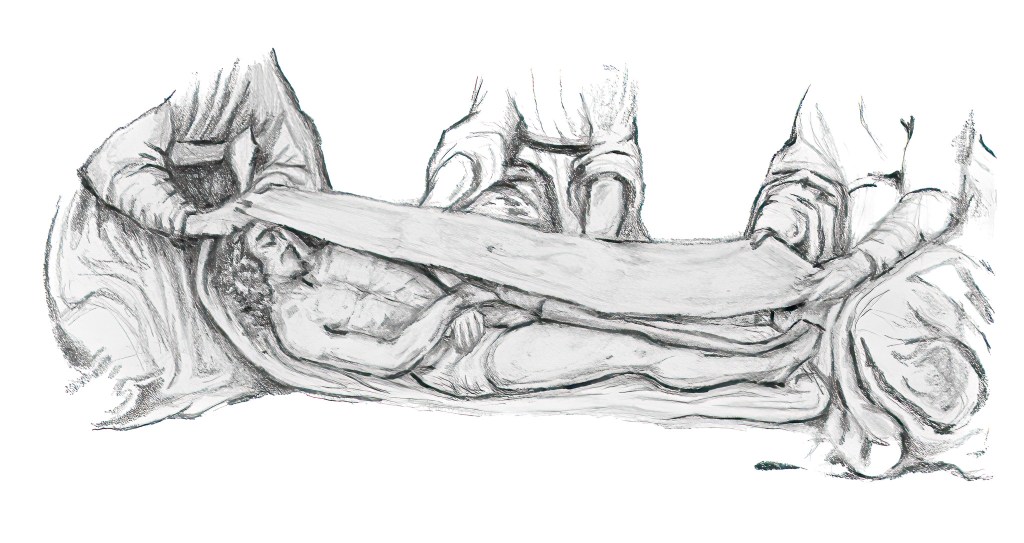

The Gospels tell us that Joseph of Arimathea went out and purchased a sindōn—a large linen cloth. This is not a collection of bandages, nor is it a fitted garment. It is a single, substantial burial shroud. The body of Jesus is then described as being “wrapped,” but not in the manner of Egyptian mummification. Jewish burial customs during the late Second Temple period involved enveloping the body in linen, more like a wrap that ran beneath the body, over the head, and back down toward the feet. A modern analogy would be closer to a folded wrap rather than layered strips.

This description aligns remarkably well with the Shroud’s dimensions and configuration. Archaeological evidence from first-century Jerusalem confirms the use of large linen shrouds, sometimes accompanied by auxiliary cloths. Thin strips, known as taeniae, were often used simply to secure the shroud in place, not to bind the body tightly. This is consistent with the Gospel language and with known burial practices of the period.

The Gospels also mention a separate face cloth, the soudarion. This is not a contradiction to the Shroud; it explains it. A face cloth would have been placed over the face immediately after death, particularly in cases involving blood loss. When the body was later prepared for burial, that cloth—already saturated with blood—would not be placed back over the face. Jewish burial law emphasized respect for blood, which was considered part of the person. A blood-soaked cloth would likely remain in the tomb, separate from the main shroud. This detail fits both the Gospel accounts and what we know of Jewish custom.

Far from conflicting with the biblical record, the Shroud fits precisely within the framework of late Second Temple Jewish burial practices, especially those attested in Jerusalem. The claim that it does not align with the Gospels simply does not hold up.

To further clarify this point, the Gospel writers themselves use specific Greek terms that align closely with known Jewish burial practices and with the type of cloth represented by the Shroud. These terms are often misunderstood or flattened in English translation, but when examined carefully, they support rather than undermine the coherence of a large burial shroud accompanied by auxiliary cloths.

• σινδών (sindōn)

Meaning: a large linen burial cloth or shroud

Used in: Matthew 27:59, Mark 15:46, Luke 23:53

This term refers to a single, substantial piece of fine linen used to wrap a body for burial. It is the primary cloth Joseph of Arimathea purchased and is fully consistent with the dimensions and function of the Shroud.

• ὀθόνια (othonia)

Meaning: linen cloths or wrappings

Used in: Luke 24:12, John 19:40, John 20:5–7

This plural term refers to linen cloths associated with burial, which may include securing bands or accompanying linens. It does not require mummy-style wrapping (which even in Egypt were no longer in use at the time of the New Testament) and fits well with the use of a main shroud held in place by auxiliary cloths or ties.

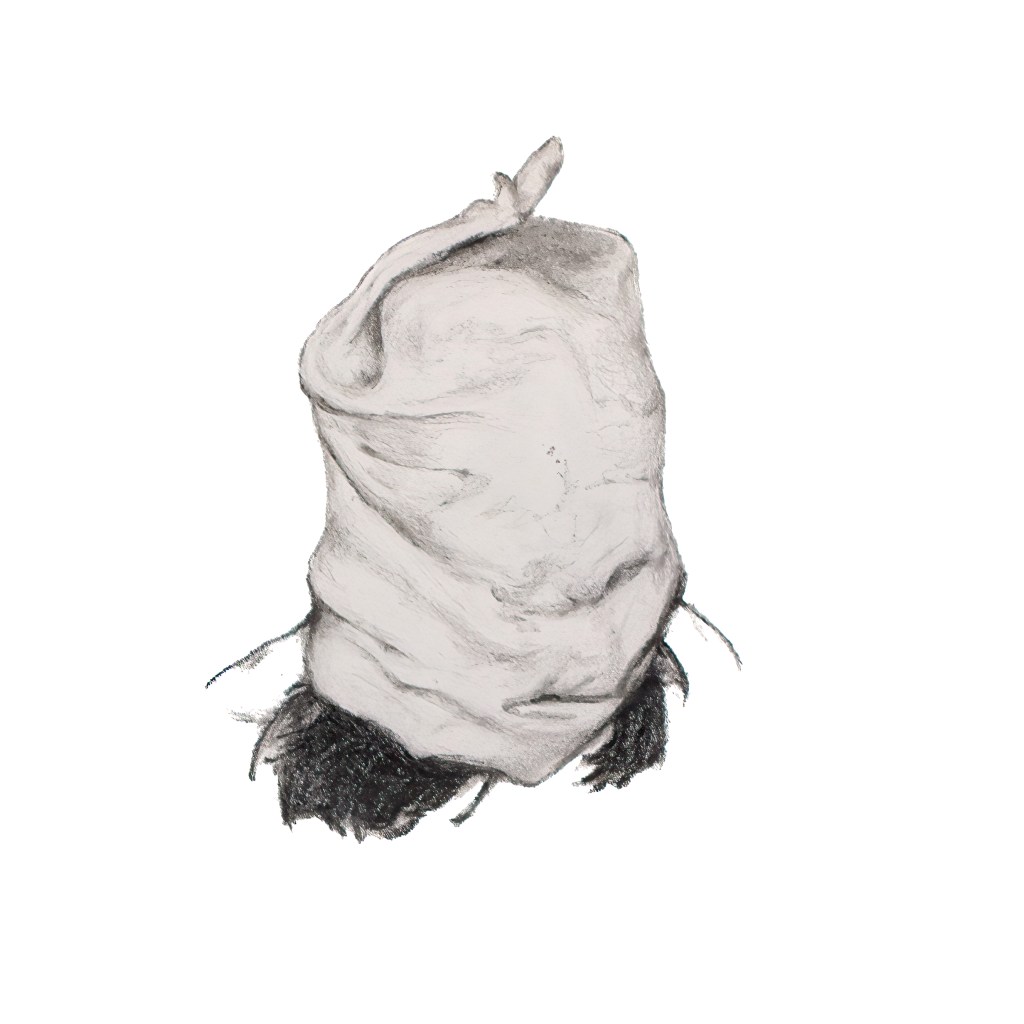

• σουδάριον (soudarion)

Meaning: face cloth or head cloth

Used in: John 11:44, John 20:7

This term refers to a separate cloth placed over the face, especially in contexts involving death or blood. Its presence as a distinct item in the tomb, folded and set apart, aligns with Jewish burial customs and explains why such a cloth would not remain on the face within the main shroud.

Taken together, these terms demonstrate that the Gospel accounts describe a burial involving a primary linen shroud accompanied by additional cloths, precisely the scenario reflected in the Shroud tradition and in Second Temple Jewish burial practices.

Objection Three: “Even If It’s Interesting, It Doesn’t Matter”

A third objection is more subtle but just as influential. Some argue that even if the Shroud is unusual, even if it is ancient, even if it aligns with crucifixion practices—it ultimately does not matter for Christian faith.

This is true in one sense and false in another. Christianity does not rest on relics. Faith is grounded in the historical resurrection of Jesus Christ, testified to in Scripture. No artifact replaces the Gospel.

But it is false to suggest that physical evidence connected to Jesus’ death and burial is therefore irrelevant. Christianity is an incarnational faith. God entered history, took on flesh, suffered, died, and rose again in space and time. Archaeology, history, and physical evidence matter precisely because Christianity makes claims about real events in the real world.

If the Shroud is authentic, it would represent the most extensively studied artifact from antiquity and the only object plausibly connected to the resurrection that bears unexplained physical properties consistent with a transformed body. Even if one remains agnostic about its authenticity, the Shroud functions as a powerful reminder that the crucifixion was not symbolic, not mythic, and not abstract. It was violent, bodily, and real.

It is important to draw a clear distinction here. The Shroud is not an object of faith, nor is belief in it required for salvation, discipleship, or orthodox Christianity. Its value is evidential and illustrative, not doctrinal. In this sense, the Shroud functions in the same category as archaeology, historical testimony, and external corroboration of biblical events. Evangelicals regularly appeal to such evidence when discussing the existence of Jesus, the crucifixion, or the reliability of the Gospel accounts. To acknowledge the potential relevance of the Shroud is simply to remain consistent with how physical evidence is already used in Christian apologetics, not to elevate an artifact above Scripture.

For evangelicals especially, the Shroud should not be feared. It does not undermine Scripture. It does not compete with the Gospel. At most, it invites further reflection on the physical reality of Christ’s death and the mystery of what happened between burial and resurrection.

For a faith rooted in real events, honest engagement with physical evidence is not a threat to belief, but a natural extension of it.

Why the Shroud Is Worth Christian Consideration

The Shroud of Turin does not demand belief. But it does deserve fair consideration. Its contested dating, unexplained image formation, anatomical precision, alignment with Jewish burial practices, and deep connection to the central claims of Christianity place it firmly within the domain of legitimate inquiry.

To reject it out of hand because of denominational associations is not discernment; it is bias. To dismiss it without engaging the evidence is not faithfulness to Scripture; it is intellectual avoidance. And to refuse even to ask whether God might have left behind a tangible witness to the crucifixion is to forget that Christianity is rooted in history, not abstraction.

Whether one ultimately concludes that the Shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus or not, it remains one of the most remarkable and challenging artifacts ever studied. And that alone makes it something all Christians can approach with humility, curiosity, and confidence—without fear, without prejudice, and without compromising the Gospel.

When we return to the starting point, the picture becomes clearer. The Shroud of Turin remains scientifically anomalous, historically contested, and yet grounded in a set of facts that cannot be waved away:

- a disputed carbon-14 date

- a superficial image confined to the outermost fibers

- real blood applied before image formation

- photographic negative behavior

- coherent three-dimensional imaging

- and a physical phenomenon that has never been reproduced

The common evangelical objections, whether rooted in denominational bias, misunderstandings of Jewish burial practices, or the assumption that physical evidence somehow threatens faith, do not withstand careful scrutiny. None of these objections negate the Shroud’s relevance, and none justify its dismissal. Christianity is a faith rooted in history, flesh, and real events. Whether one ultimately accepts or rejects the Shroud’s authenticity, it deserves to be approached not with fear or prejudice, but with intellectual honesty and theological confidence. At the very least, the Shroud asks a question no Christian should be afraid to consider: what if the Gospel left behind not only testimony, but a trace?

Leave a comment