And Joseph took thebody and wrapped it in a clean linen shroud

—Matthew 27:59 (ESV)

Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen cloths lying there, and the face cloth, which had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen cloths but folded up in a place by itself.

—John 20:6–7 (ESV)

Why are so many evangelical Christians quick to dismiss the Shroud of Turin? Perhaps it’s because we associate it with relics, or because we’re uncomfortable with anything that hints of tradition outside our familiar theological circles. But let’s take a moment to step back and ask a more basic question: Is it scriptural to consider the Shroud?

We need to set aside reactionary reflexes and follow our own principles: Is this consistent with Scripture? Does the science support it? Could this be something God is using to bring others to Christ?

A Scriptural Foundation: Three Burial Cloths, One Messiah

Let’s begin with the Bible itself. The Gospels mention multiple burial cloths:

- The sindon (shroud): A large linen sheet mentioned in Matthew 27:59, Mark 15:46, and Luke 23:53.

- The othonia (strips or wrappings): Found in Luke 24:12 and John 19:40.

- The soudarion (face cloth): Mentioned in John 20:7.

This aligns with Jewish burial practices of the Second Temple period. As I show in Sacred Threads, bodies were wrapped in a single linen sheet (sindon), with additional binding strips (othonia), and a face cloth (soudarion) placed over the head at the time of death. But that face cloth, especially if soaked in blood from a violent death, would likely have been respectfully removed before burial and placed near the body—exactly as John describes.

The Mishnah (e.g., Semahot 11.6–7) emphasizes that blood from a violent death should be buried with the body, but not necessarily kept on the face. Jewish tradition regarded blood as part of the person’s life (Leviticus 17:11), and the act of removing a blood-soaked face cloth was an expression of chesed shel emet—true kindness to the dead. Placing it at the head, separate and folded, as John notes, fits both biblical and cultural expectations.

The folding of the cloth also carries theological weight. On Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16), after the high priest completed his atoning work and entered the Holy of Holies, he would remove and set aside his bloodstained garments. Jesus, our Great High Priest (Hebrews 9:11–12), finished His atoning sacrifice, and the folded cloth in the tomb bore silent witness: the work was complete.

Evangelicals and the Shroud: The Tradition Trap

Evangelicals often emphasize sola scriptura—Scripture alone as our highest authority. Ironically, many reject the Shroud not because of what the Bible says, but because of Protestant tradition. It’s been long associated with Catholic devotion, and thus often dismissed outright as superstition.

But the Shroud was not owned by the Vatican until 1983. It had been privately held by the House of Savoy for centuries. Even when displayed before popes, it was treated with respect, not veneration. And the Catholic Church has never made a doctrinal claim about its authenticity—only that it merits reflection as a possible “mirror of the Gospel.”

Even if it had always been in Catholic hands—should that automatically disqualify it? Many of the most trusted manuscripts of the New Testament, including the Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, and texts copied by Erasmus, came through Catholic and Orthodox scribes. If we trust those as part of God’s providence in preserving His word, then we should at least be open to the possibility that the Shroud is likewise part of His witness.

Scientific Rigor and the Mystery of the Image

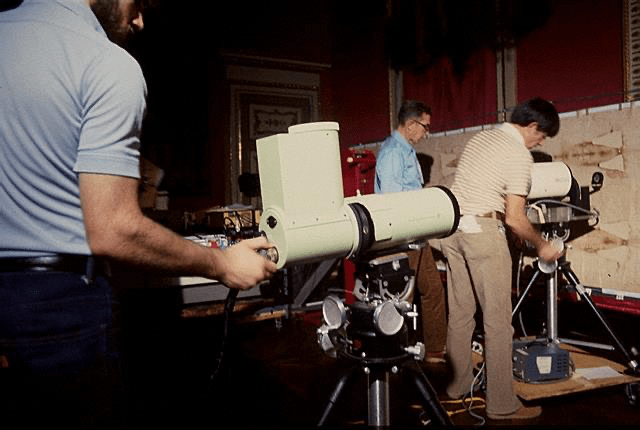

In 1978, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP)—a team of 33 scientists from Los Alamos, Sandia Labs, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and several universities—performed the most comprehensive scientific examination of the Shroud ever conducted. Their findings:

- No paint, pigment, or dye was found on the image.

- The image resides only on the outer 200 nanometers of the fibrils—far thinner than a human hair.

- The image is a photographic negative, only discovered in 1898.

- Real human blood is present, typed AB, with serum separation visible under ultraviolet light.

- The body shows anatomical accuracy consistent with Roman crucifixion:

- Wounds from a Roman flagrum

- Blood flow from wrists and feet

- Swelling from blunt trauma to the face

- A large postmortem chest wound

- The image contains 3D spatial information readable by modern topographical software—something no known artistic method can replicate.

As STURP concluded:

“The image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist.”

And to this day, no one has been able to reproduce the Shroud using any medieval or modern technique. As I detail in Sacred Threads, even today’s best lasers cannot mimic the image’s superficiality, resolution, and 3D encoding.

A Challenge to Forgers and Critics

Let’s be honest: if it’s a forgery, it’s the most advanced, foresighted, and scientifically baffling forgery ever produced.

How did a medieval artist know to depict crucifixion through the wrists—not the palms, which was the standard iconographic portrayal? How did he replicate anatomically correct scourge wounds? Why depict Jesus nude—an image considered scandalous in the Middle Ages?

Why does the cloth contain pollen from plants native only to the Jerusalem area? Why is there limestone dust on the feet and nose—matching the kind found in first-century tombs outside Jerusalem? Why use a rare 3:1 herringbone twill?

No forger would have known all this—or even thought to include such details. It’s not simply a challenge to belief; it’s a challenge to imagination.

Historical Continuity and Chain of Custody

Some critics argue there’s a gap in the Shroud’s historical record between the time of Christ and its emergence in 14th-century France. But this supposed “gap” may not be as empty as they think.

Early Eastern Christian writings speak of a miraculous image of Christ—not made by hands (acheiropoietos)—known as the Image of Edessa. It was kept folded in such a way that only the face was visible. Later, it was transferred to Constantinople. In 1204, a French knight described seeing “a cloth bearing the image of our Lord” during the sack of the city. It then disappears, only to reappear in Lirey, France, shortly thereafter.

While not ironclad, this continuity is stronger than that of many ancient manuscripts or artifacts we accept without question.

Evangelism: Can God Use a Cloth?

This is perhaps the most overlooked reason why evangelicals should not dismiss the Shroud: its potential to point people to Christ.

The Shroud has been a catalyst for spiritual reflection, conversion, and apologetic inquiry. Scientists who approached it as skeptics have walked away with questions they couldn’t ignore. Non-believers have been prompted to investigate the Gospel. Believers have had their appreciation for Christ’s suffering and resurrection deepened in profound ways.

It has no mouth, yet it speaks.

In an image-driven, skeptical, digital culture, this ancient cloth might just be the very thing that causes someone to stop, look, and ask: Did this really happen?

As one pastor told me after reading my paper:

“I wouldn’t use it to preach the resurrection—but it may get someone to open their Bible and read the resurrection accounts for the first time.”

Common Objections from Evangelicals—Gently Answered

“Isn’t this just a relic?”

It could be—but so is every archaeological artifact we use to verify the Bible. The difference is that this one might bear the image of the very One we proclaim.

“Didn’t Catholics add superstition to it?”

Possibly. But that doesn’t mean the object itself is false—only that later traditions shouldn’t control our assessment. Evangelicals don’t dismiss the New Testament because of Catholic councils. Why dismiss the Shroud because of Catholic curiosity?

“Isn’t faith about believing without seeing?”

Yes—but faith isn’t opposed to evidence. Jesus showed His wounds to Thomas. God filled the Bible with events, people, and places we can investigate. If the Shroud turns hearts toward the Gospels, then it serves the mission of faith.

A Thoughtful Wager: What Do We Risk by Considering the Shroud?

Let’s assume we know only this: the Shroud is either the burial cloth of Christ . . . or it is not. In that light, the chance might seem 50/50. But as with Pascal’s famous wager about God, the weight of the outcome makes even a modest possibility worth serious attention.

If we recognize it as authentic, then we are holding something profoundly special—an artifact that not only reveals the unimaginable suffering Jesus bore for our iniquities, but also confirms numerous details found in Scripture. It becomes not a relic, but a tangible echo of redemptive history—one that harmonizes archaeology, prophecy, and testimony.

And what if, in the end, it isn’t the burial cloth of Jesus? Then we are still left with a cloth that:

- Contains an image no one can replicate

- Matches first-century Jewish burial customs

- Has blood with postmortem indicators and high bilirubin levels consistent with trauma

- Was wrapped around a dead body in rigor mortis

- Shows no signs of decomposition

- Is at least 2,000 years old by multiple scientific methods

- Still points us to the cross and resurrection of Christ

In other words, we lose nothing. We gain a powerful reflection. We gain reverence. We gain another reason to worship—not the cloth, but the One whose image and wounds it portrays.

But this wager isn’t even 50/50. The evidence tilts the scale far further toward authenticity:

- The Scriptures describe a sindon—a linen shroud

- The Shroud fits first-century burial materials and customs

- The bloodstains came before the image

- The image is anatomically correct, forensically accurate, and chemically unexplainable

- The cloth contains no signs of pigment, brushwork, or decomposition

So if we accept pottery shards, ossuaries, or ancient manuscripts as testimony to biblical truth, why wouldn’t we at least consider a cloth that claims to hold the image and blood of the Crucified?

In the end, we must not worship the Shroud. But we should worship the One whose suffering it might reveal. And whether it proves to be the burial cloth of Jesus or not—it undeniably leads us to reflect on His suffering, His death, and His resurrection.

A Call to Humble Curiosity—and Evangelical Integrity

Evangelicals love truth. We proclaim the resurrection. We believe in biblical evidence. And yet, when presented with a cloth that might bear witness to the very thing we preach, many turn away—not because of facts, but because of fear.

Here’s what I propose:

- Start with Scripture. The Gospels mention three cloths—sindon, othonia, and soudarion. Let the text guide you.

- Weigh the science. STURP’s findings have withstood decades of scrutiny. The image still defies explanation.

- Acknowledge the history. The Shroud’s documented past is richer than many assume.

- See its evangelistic potential. If this gets someone reading the Bible, why resist it?

We are not called to worship a cloth. But we are called to worship the One it may reveal.

The Shroud may not be the burial cloth of Jesus. But it might be.

Dismissal without investigation is not discernment. It’s prejudice.

Let us be Bereans again—searching the Scriptures, weighing the evidence, and asking: Could God have left us a visual reminder of the greatest event in human history?

The tomb was empty.

The cloth was folded.

And the image of love remains.

Leave a comment