“His body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but thou shalt surely bury him that day… that thy land be not defiled.”

—Deuteronomy 21:23

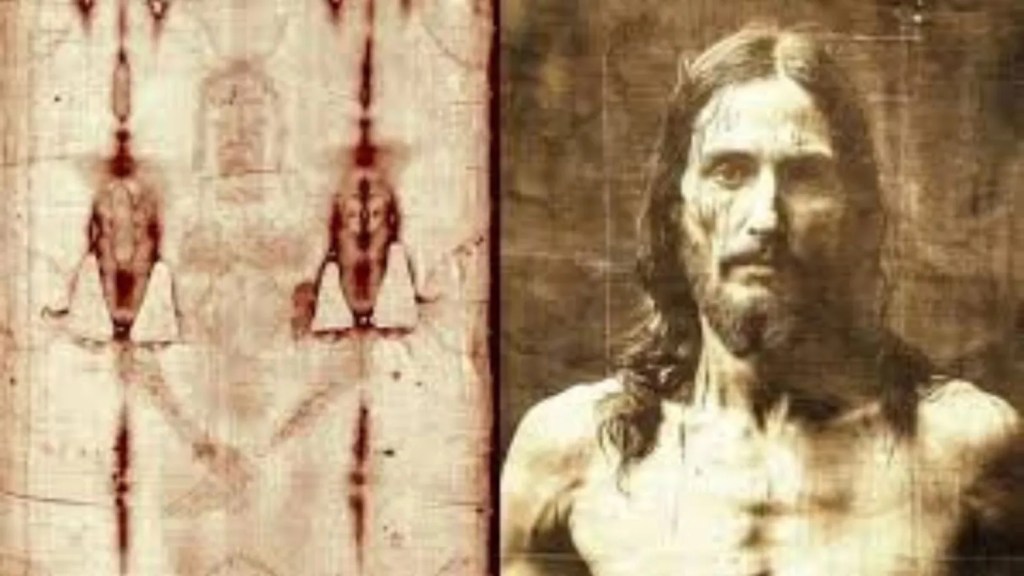

The Shroud of Turin has been examined under the lens of science, theology, art, and history. Yet one foundational question remains at the heart of the debate: Who was the man it once wrapped? While discussions often focus on theological identity, the cloth itself reveals a clear historical, cultural, and ethnic profile. Based solely on the physical, forensic, botanical, textile, and burial data, the image represents a Jewish man from first-century Judea.

This article outlines ten lines of evidence that independently and collectively support this conclusion, grounded in Jewish law (halakhah), Second Temple burial practices, and forensic science.

1. Buried in a Shroud, Not in Clothing – Consistent with Jewish Practice

The man in the Shroud is entirely nude beneath the linen cloth, yet his body is fully covered. This matches first-century Jewish burial customs, which mandated that the dead be buried not in clothing, but in simple linen shrouds (sadin, tachrichin)—regardless of wealth or status.

The Babylonian Talmud recounts how Rabban Gamliel II requested burial in plain linen, sparking a widespread shift toward simple, uniform shrouds for all Jews:

“Formerly, the expense of burying the dead was harder on the family than death itself… until Rabban Gamliel came and commanded that he be buried in a plain linen shroud…”

—Moed Katan 27b¹

The Mishnah and Dead Sea Scrolls affirm this as normative: the body was stripped of clothing, washed (unless martyred), and wrapped in linen.² No sewn garments, belts, or tunics appear on the Shroud, and forensic imaging reveals no folds, seams, or waistlines—just a full-body linen wrap, precisely as described in Jewish burial law.³

2. Unwashed Body with Preserved Blood – Halakhic Burial for Martyrs

The Shroud contains clear bloodstains at the wrists, scalp, back, and feet. Ultraviolet light reveals serum rings, indicating the blood clotted on the body and was not washed away. This is critical. While Jewish law normally required that a body be washed before burial (Mishnah Moed Katan 1:6), a violent death altered that procedure.

According to Semahot 8.1, when someone dies a bloody or unjust death, the blood must be buried with the body. It is part of their personhood.⁴

“One who dies a violent death is not washed, for his blood is his soul.”

This is exactly what we see on the Shroud. It reflects Jewish legal care, not Roman indifference. Whoever buried this man did so in accordance with Torah and Mishnah—seeing him not as a criminal, but as a martyr to be honored.

3. The Beard and Sidelocks – Grooming That Aligns with Torah

The man’s face shows a natural, untrimmed beard and long side hair, which fall toward the chest. This aligns with Leviticus 19:27: “Do not round off the hair at your temples or mar the edges of your beard.” This verse was taken seriously in Second Temple Judaism.⁵

Philo of Alexandria, writing in the first century, notes:

“The beard is the mark of a free man. The Jew never shaves it, holding it in reverence as nature’s adornment.”⁶

By contrast, Romans and Greeks often shaved or groomed their beards and wore short hair. The image on the Shroud presents a man whose grooming habits fit those of a Torah-observant Jew, not a Greco-Roman artisan or soldier.

4. Textile Analysis – Ritually Clean Linen Consistent with Jewish Law

The Shroud is composed of a three-over-one herringbone linen weave. It contains no wool, which is important because Jewish law forbade mixing wool and linen in garments (shaatnez; cf. Deut. 22:11).

Swiss textile expert Mechthild Flury-Lemberg concluded that the Shroud’s quality and weave are consistent with first-century eastern Mediterranean loom technology, likely from Syria or Judea.⁷

The absence of impurities or patching, and the ritual cleanliness of the cloth, reinforce that this was not a reused or random wrapping. It fits the Jewish mandate for burial in clean linen—especially for someone seen as devout or honorable.⁸

5. No Embalming or Pagan Burial Practices

Scientific analysis of the cloth—by the 1978 STURP team and others—shows no trace of embalming agents. No natron, no preservatives, no wax or resin. This rules out Egyptian and Greco-Roman styles of mummification.

Instead, this matches Jewish burial custom, which prohibited embalming and treated death as a return to dust (Gen. 3:19).⁹

Also absent are coins, amulets, statues, or charms—common in Roman graves. Jewish burial law strictly forbade graven images and required ritual purity in death as in life (Mishnah Semahot 12:8–9).¹⁰

6. Spices Found on the Cloth – Not for Embalming, But Honor

Chemical analysis has found traces of aloes and myrrh, particularly around the feet and back. These were not preservatives, but honorific spices used in Jewish burial to mask odor and show reverence—just as John 19:39 describes.

Josephus confirms: “The body was anointed with perfumes and spices, not to embalm it, but to honor it.”¹¹

Their presence confirms this man was not discarded, but respected and buried with Jewish reverence.

7. Prompt Burial – Jewish Law Required Same-Day Interment

The absence of decomposition confirms the body was buried within 24 hours. Decomposition artifacts like bloating, discoloration, or skin slippage are completely missing.

This fits Jewish law: “You must bury him the same day… for anyone hung on a tree is under God’s curse” (Deut. 21:23). The Mishnah affirms that executed criminals were to be buried quickly and respectfully (Mishnah Sanhedrin 6:5).¹²

Romans left bodies exposed for days. This man, by contrast, was buried quickly and with dignity—indicating Jewish care, not Roman neglect.

8. Respectful Body Position – Hands Covering Genitals

The man’s hands are crossed over the pelvic region, fingers extended, not bound. This modest pose aligns with Jewish burial norms emphasizing respect for the body, even in death. Romans had no such concerns.

The Talmud teaches that the human body must be treated with honor, covered, and returned to God in purity (Berakhot 19a).¹³

9. Anthropological Facial Features – Consistent with First-Century Judeans

Facial analysis by Barbet, Lavoie, and Borrini confirms Semitic features: a strong nasal bridge, deep-set eyes, and high cheekbones. These match skulls from first-century ossuaries in Jerusalem, including the “Caiaphas tomb” and Talpiot tomb.¹⁴

These are not European or African craniofacial traits, but Levantine Jewish features—consistent with the region and ethnicity of the man.

10. Pollen and Plant Traces Specific to Jerusalem

Botanical studies by Max Frei and Prof. Avinoam Danin show that the Shroud contains pollen from 28 plant species, 14 of which grow only in Jerusalem or its surroundings, and bloom around Passover (March-April).

Notably, Gundelia tournefortii—a thorny plant—was found around the head region, supporting the crown-of-thorns tradition.¹⁵

No medieval European forger could have included such precision. The evidence places the cloth in Jerusalem, during spring, and the pollen matches Jewish burial during Passover season.

Conclusion: A Torah-Observant Jewish Man Buried with Honor

Whoever the man of the Shroud was, he bore the cultural, anatomical, legal, and ritual hallmarks of a first-century Jew:

- He was buried naked but wrapped in linen

- His body was not washed because he died violently

- He wore a beard and sidelocks in accordance with Leviticus

- He was honored with spices, not embalmed

- He was buried quickly, modestly, and in accordance with Torah

The Shroud bears no Roman or pagan symbolism, no anachronisms, no artificial enhancements. It bears only the silent witness of a man, wrapped in reverence, mourned in haste, and honored according to the Law of Moses.

If the Shroud is a forgery, then it is a forgery of such cultural and halakhic accuracy that it surpasses the knowledge of any known medieval forger. If it is authentic, then it is what it appears to be: the burial cloth of a Jewish man crucified and buried in first-century Judea, by Jewish hands, in Jewish soil, under Jewish law.

“Who do you say that I am?”

—Jesus, Matthew 16:15

Footnotes

- Babylonian Talmud, Moed Katan 27b

- Mishnah Semahot 12:7–9; Moed Katan 1:6

- Temple Scroll (11QT) 48:16–18, Dead Sea Scrolls

- Mishnah Semahot 8:1

- Leviticus 19:27

- Philo of Alexandria, Special Laws I.142

- Flury-Lemberg, Mechthild. “Textile Aspects of the Shroud of Turin.” Textile History 1998

- Rachel Hachlili, Jewish Funerary Customs, Brill, 2005

- Gen. 3:19; cf. Josephus, Antiquities 17.199

- Mishnah Semahot 12:8–9

- Josephus, Jewish War 2.199

- Mishnah Sanhedrin 6:5

- Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 19a

- Borrini, Matteo et al., “Craniofacial Identification and the Turin Shroud,” J. Forensic Sci. (2022)

- Danin, Avinoam, Botany of the Shroud, 1999

Leave a comment