And Why Modern Christianity Is Uncomfortable With It

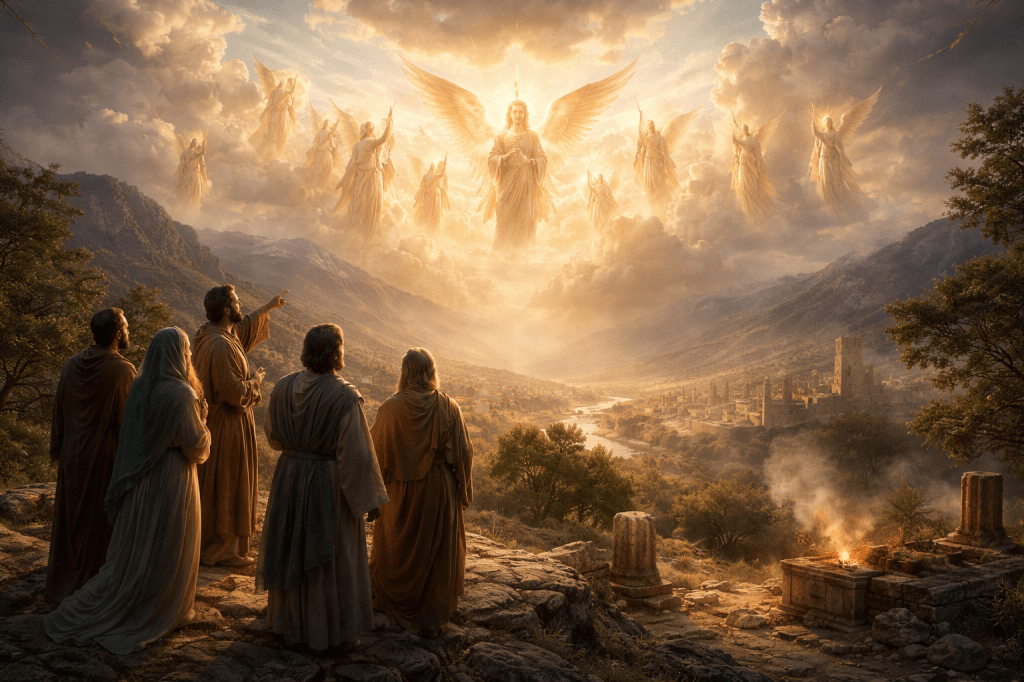

Modern readers often approach the Bible with a quiet but powerful assumption: that while supernatural events may have happened then, they do not meaningfully happen now. In the process, we tend to de-spiritualize Scripture, treating angels, spirits, divine encounters, and cosmic conflict as relics of a distant past rather than as elements of a living worldview. Yet the Bible is unapologetically supernatural. Just as it records history, poetry, prophecy, biography, and law, it also records a vision of reality in which the unseen is real, active, and consequential. The world of the Bible — especially the world of ancient Israel and Second Temple Judaism — would have found it strange, if not outright unfaithful, to affirm the text while dismissing the supernatural framework it assumes. The biblical authors, the prophets, the disciples, and Jesus Himself did not merely seek correct doctrine; they inhabited a reality populated by God, angels, spirits, and powers beyond human sight. If we are to read Scripture faithfully, we must approach it as it was originally written and heard — not with modern skepticism imposed upon it, but with eyes open to the supernatural world it consistently reveals.

The Disciples, Ghosts, and the World Scripture Assumes

When the disciples saw Jesus walking on the water, Matthew tells us they cried out in fear, saying, “It is a ghost!” (Matthew 14:26). Luke records something similar after the resurrection, when the risen Christ appeared among them: “They were startled and frightened and thought they saw a spirit” (Luke 24:37). These reactions are often read quickly and dismissed as momentary confusion, as though the disciples were merely panicking fishermen or emotionally overwhelmed followers. Yet this reading misses the deeper implication of the text. The disciples did not debate whether ghosts or spirits existed. They assumed such beings were real. Their fear was not rooted in skepticism but in recognition. Their mistake was not metaphysical but identificational. They misidentified what they were seeing, not the category of being they believed could exist.¹

This matters because it shows us the default worldview of Jesus’ closest followers. These were not naïve pagans, but first-century Jews steeped in Scripture. Their instinctive reaction reveals how deeply embedded belief in spirits was within the biblical imagination. Scripture never pauses to correct their belief in spirits as such. Instead, Jesus corrects their misunderstanding by saying, “A spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have” (Luke 24:39). The correction assumes the category of spirits is valid. What Jesus clarifies is that He is not one of them. This detail alone should give modern readers pause. The biblical text does not share our discomfort with the supernatural. It assumes a world where such realities are part of normal experience.²

An Enchanted Cosmos: Spirits as a Normal Category of Reality

From Genesis to Revelation, the biblical authors inhabit what might rightly be called an enchanted cosmos. Heaven and earth are not sealed compartments but overlapping realms that constantly interact. God is not merely the highest being within a closed natural system, but the sovereign ruler of a populated spiritual world that intersects with human history in real and consequential ways. Angels appear, demons speak, visions intrude into ordinary life, and spiritual beings act with intention and agency. This worldview is not limited to obscure or marginal texts. It runs through the Law, the Prophets, the Writings, the Gospels, and the Epistles.³

One of the clearest indicators of this worldview is how casually Scripture treats disembodied spirits. Job describes a spirit passing before his face, causing physical fear (Job 4:15). Isaiah portrays the dead as stirred in Sheol, conscious and responsive (Isaiah 14:9–10). Jesus speaks of unclean spirits wandering through waterless places and seeking rest (Matthew 12:43) as though this were common knowledge. None of these passages signal that such descriptions are symbolic or psychological. They assume a shared understanding between author and audience. Spirits are part of the ontology of the biblical world. Modern Christians often feel pressure to explain these texts away, but this impulse arises from cultural discomfort, not from the text itself.⁴

The Unseen Realm Revealed: Elisha and the Opening of Spiritual Sight

One of the clearest narrative illustrations of this supernatural worldview appears in the account of Elisha and his servant in 2 Kings 6. When the Aramean army surrounds the city, Elisha’s servant panics, seeing only overwhelming physical danger. Elisha, however, remains calm and prays, “O LORD, please open his eyes that he may see.” When the servant’s eyes are opened, he sees the hills filled with horses and chariots of fire surrounding Elisha. The text is explicit: nothing new is created in that moment. No angelic army suddenly arrives. The unseen reality was already present. What changed was perception. Scripture presents the supernatural realm not as distant or imaginary, but as ordinarily invisible, intersecting the physical world at every moment.

And if one is tempted to think such accounts belong only to the ancient world, it may be worth listening to those who have served on foreign mission fields, particularly in regions not buffered by Western materialism. Missionaries across Africa, Asia, and parts of the Middle East have long testified, often reluctantly and cautiously, of moments where protection, deliverance, or restraint seemed to come from beyond what could be explained by human means alone. Whether described as unseen barriers, sudden fear falling on aggressors, or the sense of being inexplicably “surrounded,” such accounts echo the biblical pattern: not the creation of new spiritual realities, but brief glimpses into what was already there. This episode powerfully reinforces a central biblical assumption: reality is not limited to what human senses naturally perceive, and God’s people are often far more surrounded than they realize.

New Testament scholar Craig Keener documents multiple cases from Mozambique during the late twentieth century in which rebel forces reported seeing armed guards surrounding Christian villages, only to retreat in fear—despite no human defenders being present. In several cases, these claims came not from believers seeking to interpret events spiritually, but from the attackers themselves after capture. Whatever one ultimately concludes about such reports, they closely mirror what is described in 2 Kings 6: not the creation of new spiritual realities, but momentary disclosure of what was already there.²

The Divine Council and Biblical Monotheism

Closely connected to this enchanted worldview is the biblical concept of the divine council. Several passages depict God presiding over an assembly of heavenly beings who participate, in subordinate ways, in His governance of the cosmos. Psalm 82 opens with the striking declaration, “God has taken his place in the divine council; in the midst of the gods he holds judgment,” before announcing judgment upon these beings for their injustice (Psalm 82:1–2). In Job, we are told that “the sons of God came to present themselves before the LORD,” a scene that assumes an existing heavenly assembly accountable to Yahweh (Job 1:6; 2:1). In 1 Kings 22, the prophet Micaiah recounts a vision in which he “saw the LORD sitting on his throne, and all the host of heaven standing beside him,” as deliberation takes place concerning events that will unfold on earth (1 Kings 22:19–22). Daniel similarly describes a courtroom scene in which “thrones were placed,” “the Ancient of Days took his seat,” and “the court sat in judgment,” surrounded by countless heavenly attendants (Daniel 7:9–10). These scenes are not isolated poetic flourishes or metaphorical embellishments. They form a consistent and coherent pattern across the Old Testament, presenting a heavenly administration under the supreme authority of God.⁵

Modern readers often stumble at these texts because they appear to challenge monotheism. Yet biblical monotheism was never about denying the existence of other spiritual beings. It was about denying their equality with Yahweh. Scripture consistently affirms that only one being is uncreated, eternal, and worthy of worship. The others, however exalted, are contingent, subordinate, and accountable. Psalm 82 itself makes this clear when God declares judgment upon the divine beings, reminding them that despite their status, they will “die like men” (Psalm 82:7). Recognizing this framework actually strengthens monotheism rather than weakening it. God is not threatened by the existence of other spiritual beings any more than a king is threatened by having servants. When modern theology flattens these scenes into metaphor, it does so not because Scripture demands it, but because later philosophical categories — shaped by post-Enlightenment assumptions—struggle to accommodate the Bible’s own supernatural worldview.⁶

Spiritual Geography and Cosmic Powers Over Nations

The Bible also presents a vision of the world in which geography itself has spiritual significance. Nations are not merely political or ethnic entities. They are associated with spiritual powers and placed within a larger cosmic order. Deuteronomy 32 states that “when the Most High gave to the nations their inheritance, when he divided mankind, he fixed the borders of the peoples according to the number of the sons of God, but the LORD’s portion is his people, Jacob his allotted heritage” (Deuteronomy 32:8–9). Preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Septuagint, this text situates the division of the nations within a supernatural framework. Humanity is not merely scattered by geography or chance. The distribution of the nations occurs under divine authority and spiritual administration, while Israel is uniquely reserved for Yahweh Himself. Human history, in this view, unfolds within a cosmic order that is neither accidental nor spiritually neutral.⁷

Daniel 10 makes this worldview explicit by describing angelic “princes” over Persia and Greece who resist God’s messengers. Paul draws directly on this framework when he tells believers that their struggle is not against flesh and blood but against rulers and authorities in the heavenly places (Ephesians 6:12). This means spiritual warfare in Scripture is not limited to personal temptation or moral struggle. It includes cosmic conflict that plays out through historical events. When modern Christianity reduces spiritual warfare to internal psychology, it loses this larger biblical vision. The mission of the church, in this light, becomes more than personal salvation; it is participation in God’s reclaiming of a world fractured by rebellion.⁸

Nephilim, Angelic Rebellion, and Avoided Texts

Few passages make modern readers more uncomfortable than those dealing with the Nephilim and angelic rebellion, largely because they resist easy categorization within later theological systems. Genesis 6 describes a moment of profound transgression prior to the flood, stating that “the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose,” and that “the Nephilim were on the earth in those days” and were known as “the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown” (Genesis 6:1–4). The passage is deliberately brief, but it clearly links the presence of the Nephilim with a period of escalating corruption and violence that culminates in divine judgment. The text does not explain away the identity of the sons of God, nor does it signal that this language should be read metaphorically. It assumes a supernatural transgression that disrupts the created order.

This episode is not isolated to Genesis. Numbers 13 records the report of the Israelite spies who claim, “We saw the Nephilim there,” describing themselves as grasshoppers by comparison (Numbers 13:33). Whether one interprets this report as exaggerated or literal, the text assumes that the Nephilim were understood as real beings associated with extraordinary size and power. By the Second Temple period, these passages were widely interpreted as referring to a rebellion by heavenly beings. Jewish texts such as 1 Enoch, which was not fringe literature but widely read and respected, expanded on Genesis 6 by portraying the sons of God as angelic beings whose actions corrupted humanity and introduced violence, injustice, and forbidden knowledge into the world. This interpretive tradition formed part of the intellectual and theological environment of first century Judaism, the same world inhabited by Jesus, the apostles, and the earliest Christians.⁹

Crucially, the New Testament does not correct or reject this worldview. Instead, it alludes to it. Jude speaks of “the angels who did not stay within their own position of authority, but left their proper dwelling,” stating that they are now kept in eternal chains under gloomy darkness until judgment (Jude 6). He later explicitly references the prophecy of Enoch, showing familiarity with this Second Temple tradition (Jude 14–15). Peter likewise refers to angels who sinned, saying that God “did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into Tartarus and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness” (2 Peter 2:4). These references are brief, but they are theologically loaded. They assume a shared narrative of angelic rebellion that extends beyond human sin alone.

Modern Christians often avoid these texts because they do not fit neatly into later systematic categories or because they sound strange to ears shaped by modern naturalism. Yet avoiding them weakens our understanding of evil itself. Scripture presents rebellion as both human and cosmic, moral and spiritual. Human violence and corruption are not portrayed as arising in a vacuum but as occurring within a wider context of supernatural disorder. Reducing evil to psychology, sociology, or personal moral failure alone strips the biblical story of its depth and scope. The Bible’s account of redemption, by contrast, addresses a fractured creation at every level, reclaiming what was distorted not only by human disobedience, but by cosmic rebellion as well.¹⁰

Angels, Fear, and the Loss of Otherness

Angels in Scripture are not gentle, sentimental figures meant to reassure by their familiarity. They are fear inducing beings whose presence regularly overwhelms human senses and disrupts ordinary experience. When Manoah realizes that he and his wife have encountered the angel of the LORD, he cries out in terror, “We shall surely die, for we have seen God” (Judges 13:22). His fear is not irrational or rebuked by the text. It reflects the biblical assumption that close proximity to the divine is dangerous for mortal creatures. Ezekiel’s encounter with heavenly beings is even more arresting. He describes living creatures with multiple faces, wings, wheels within wheels full of eyes, radiant fire, and deafening sound. When he sees the vision of the glory of the LORD, he falls facedown in awe and fear (Ezekiel 1:28). Isaiah likewise recounts his vision of the LORD seated on a throne, surrounded by seraphim calling out “Holy, holy, holy.” His immediate response is not comfort but dread. “Woe is me,” he cries, “for I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips” (Isaiah 6:1–5). In each case, the encounter with heavenly beings produces fear, disorientation, and an acute awareness of human unworthiness.

The frequent biblical command “Do not fear” appears in this context, not because angels are harmless, but because fear is the natural and expected response to encountering the supernatural. When Gabriel appears to Zechariah, Luke tells us that “fear fell upon him,” prompting the angel to say, “Do not be afraid” (Luke 1:12–13). The same pattern occurs with Mary, the shepherds, and others who encounter angels. The command to not fear does not negate the otherness of angels. It acknowledges it. Scripture consistently portrays the supernatural as weighty, unsettling, and holy rather than familiar or sentimental.¹¹

Modern Christian imagination has largely stripped angels of this otherness. They have been reshaped into comforting symbols, artistic decorations, or therapeutic figures meant to inspire calm rather than reverence. This shift reflects modern cultural sensibilities far more than biblical fidelity. In Scripture, angels are not designed to make people feel safe. They reveal the nearness of God, and that nearness is overwhelming. When angels are domesticated, holiness itself is diminished. The biblical witness repeatedly links the supernatural with glory, danger, and awe, emphasizing that approaching God is never casual or trivial. Recovering this sense of otherness restores a posture of reverence that Scripture consistently commends and that modern faith too often lacks.¹²

The Angel of the LORD and Divine Complexity

The figure known as the Angel of the LORD presents one of the most intriguing and theologically rich tensions in Scripture. This figure is repeatedly identified with God and yet distinguished from God, speaking with divine authority while also being sent by the LORD. In Genesis 16, the Angel of the LORD appears to Hagar in the wilderness and speaks promises that only God can make. After the encounter, Hagar names the LORD who spoke to her, saying, “You are a God of seeing,” explicitly identifying the Angel with Yahweh Himself (Genesis 16:7–13). In Genesis 22, the Angel of the LORD calls to Abraham from heaven and declares, “By myself I have sworn, declares the LORD,” speaking in the first person as God while also referring to God as the one who sent him (Genesis 22:11–18). At the burning bush in Exodus 3, Moses encounters “the Angel of the LORD” appearing in a flame of fire, yet the text immediately states that “God called to him out of the bush,” and Moses is told to remove his sandals because the ground is holy, a response appropriate only to the direct presence of God (Exodus 3:2–6).

This same pattern continues in the book of Judges. In Judges 6, the Angel of the LORD appears to Gideon, receives an offering, and causes fire to consume it. Gideon responds in fear, crying out, “Alas, O Lord GOD! For now I have seen the Angel of the LORD face to face,” and the LORD reassures him, “Peace be to you. Do not fear; you shall not die” (Judges 6:22–23). In Judges 13, the Angel of the LORD appears to Manoah and his wife, ascends in the flame of the altar, and prompts Manoah to declare, “We shall surely die, for we have seen God” (Judges 13:20–22). In each of these encounters, the Angel is not treated as a mere messenger. He speaks as God, bears the divine name, receives worship, and inspires fear appropriate to the divine presence, while still being described as sent by the LORD. These encounters resist simplistic explanation and press the reader to grapple with a complexity in God’s self manifestation that Scripture does not attempt to resolve prematurely.¹³

Early Christians recognized that these passages prepared the conceptual ground for later Trinitarian reflection. They did not invent complexity where none existed but responded to patterns already present in the biblical text. The Angel of the LORD passages demonstrate that God’s self revelation cannot be reduced to a single flat category. God is one, yet He makes Himself known in ways that involve distinction within His own identity. Modern readers often gloss over these texts because they do not fit neatly into later theological formulas or because they introduce tensions that resist easy classification. Yet Scripture itself is not embarrassed by this complexity. It presents these encounters without apology, inviting careful reflection rather than avoidance. To read the Bible faithfully is not to force it into simplified categories, but to allow its own patterns of revelation to shape our understanding of who God is and how He makes Himself known.¹⁴

Blessings, Curses, and the Power of Words

In Scripture, words are not merely descriptive statements about reality. They are effective acts that participate in shaping reality. Blessings and curses are treated as real forces with tangible consequences. This worldview is made especially clear in the account of Balaam in Numbers 22–24. Though hired to curse Israel, Balaam repeatedly confesses that he is powerless to do so, declaring, “How can I curse whom God has not cursed? How can I denounce whom the LORD has not denounced?” (Numbers 23:8). Even when pressured by Balak, Balaam insists that he can only speak what God puts in his mouth, and what God has spoken over Israel is blessing, not curse. Balaam concludes, “He has blessed, and I cannot revoke it” (Numbers 23:20). The text assumes that spoken blessing and curse are not symbolic gestures but binding realities rooted in divine authority.

This same assumption governs the covenant structure of Deuteronomy 28, where blessings and curses are laid before Israel as operative realities that will shape the nation’s future. Obedience results in blessing that overtakes the people, while disobedience brings curses that pursue and overtake them (Deuteronomy 28:2, 15). These are not merely moral consequences in the abstract. They are described as active forces affecting fertility, land, security, exile, and restoration. The covenantal framework presumes that words spoken by God carry causal power and that human participation in covenant speech, whether through oath or rebellion, aligns individuals and nations with those realities. Scripture consistently treats speech as a vehicle of spiritual causality rather than a neutral exchange of information.¹⁵

Paul’s declaration that Christ became a curse for us only makes sense within this biblical framework. Quoting Deuteronomy, Paul writes, “Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree,” and then concludes, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us” (Galatians 3:13). This language assumes that curse is not a metaphorical label but a covenantal condition that can be borne, transferred, and undone through divine action. If curses were merely symbolic or psychological, Paul’s argument would collapse. Redemption, in Scripture, is not only forgiveness of guilt but deliverance from a real covenantal condition that binds humanity under judgment. Modern culture tends to treat words as subjective expressions or emotional signals, but Scripture treats them as solemn acts that invoke blessing or judgment. Recovering this view helps explain why Scripture places such weight on oaths, vows, blessings, proclamations, and even warnings, all of which operate within a world where speech participates in God’s active governance of reality.¹⁶

Conscious Dead and the Intermediate State

Scripture consistently portrays the dead as conscious and aware rather than dissolved into unconscious nonexistence. Isaiah vividly depicts the realm of the dead as stirred by the arrival of a fallen king, declaring that “Sheol beneath is stirred up to meet you when you come,” and that the shades of the dead rise and speak, saying, “You too have become as weak as we” (Isaiah 14:9–10). The language assumes awareness, recognition, and response among the dead. This same assumption appears in the teaching of Jesus. In His parable of the rich man and Lazarus, Jesus describes both figures as conscious after death, capable of memory, speech, moral awareness, and expectation of future judgment. The rich man is said to be in anguish, fully aware of his condition and of Lazarus’ comfort, while Lazarus is depicted as comforted in Abraham’s bosom (Luke 16:19–31). Whatever one’s interpretation of the genre of this parable, Jesus clearly assumes post mortem consciousness and moral continuity rather than annihilation or soul sleep.

The book of Revelation reinforces this perspective by portraying the souls of martyrs as consciously present before God. John sees “the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God,” and hears them crying out, “O Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before you will judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?” (Revelation 6:9–10). These souls are aware of injustice, capable of speech, and awaiting divine action. Scripture does not offer a systematic explanation of the intermediate state, nor does it answer every metaphysical question about the nature of post death existence. Yet across genres and testaments, it consistently rejects the notion that death results in unconscious nonexistence. The dead remain conscious participants within God’s unfolding purposes.¹⁷

This biblical portrayal directly challenges modern materialist assumptions about human nature. Scripture does not treat human identity as reducible to the physical body alone. While bodily resurrection is central to biblical hope, the Bible assumes continuity of personal identity between death and resurrection. The dead are not portrayed as erased or suspended but as existing within God’s economy in a conscious state. Scripture operates within a worldview that affirms ongoing awareness beyond physical death. Ignoring this dimension distorts biblical anthropology by importing modern assumptions into a text that consistently presents human beings as more than merely biological organisms.¹⁸

Cosmic Rebellion and the Scope of Redemption

All of these threads converge in Scripture’s portrayal of cosmic rebellion. Evil is not presented merely as human failure or moral weakness, but as participation in a wider revolt against God’s created order. This pattern appears at the very beginning of the biblical story. In Genesis 3, the serpent enters the garden as a deceptive, non human agent who opposes God’s word and draws humanity into rebellion. The conflict introduced there is not only between humans and God, but between God and a spiritual adversary whose influence extends beyond individual temptation. Scripture continues this theme throughout its narrative. Jesus later refers to Satan as “the ruler of this world,” describing him as an active power whose authority is real but temporary and destined for judgment (John 12:31; 14:30; 16:11). History, in the biblical worldview, unfolds within contested space where divine purpose and rebellious powers collide.

Psalm 82 makes this cosmic dimension explicit by portraying God standing in judgment over other divine beings. God declares, “I said, ‘You are gods, sons of the Most High, all of you; nevertheless, like men you shall die, and fall like any prince’” (Psalm 82:6–7). The psalm depicts these beings as having failed in their responsibilities, contributing to injustice and disorder on the earth, and now facing divine judgment. This scene reinforces the idea that rebellion is not confined to humanity alone but extends into the spiritual realm. The New Testament assumes this same framework. Paul declares that Christ, through His death and resurrection, has decisively confronted these hostile powers, stating that God “disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him” (Colossians 2:15). The cross is presented not only as a means of individual forgiveness, but as a public defeat of cosmic enemies who had exercised real authority within the fallen order.¹⁹

Redemption, therefore, is not merely the cancellation of personal guilt. It is cosmic victory. Christ’s resurrection signals not only hope for individual believers but the beginning of the restoration of all creation. Paul proclaims that Christ must reign “until he has put all his enemies under his feet,” culminating in the destruction of death itself (1 Corinthians 15:25–26). Creation, Paul explains elsewhere, is presently groaning, awaiting liberation from its bondage to corruption, a liberation tied directly to the revealing of God’s redeemed people (Romans 8:19–22). When the supernatural framework of Scripture is removed, salvation is easily reduced to moral improvement, therapeutic self help, or private spirituality. When that framework is restored, the gospel regains its full scope and power. It is the announcement that God, in Christ, has begun reclaiming a world fractured by rebellion at every level, human and cosmic alike.²⁰

Why Modern Christianity Is Uncomfortable With This Worldview

The discomfort many Christians feel toward the Bible’s supernatural worldview is largely historical rather than biblical. Beginning in the Enlightenment, Western thought increasingly privileged empirical reason as the primary avenue to knowledge and elevated methodological skepticism as a virtue. Reality came to be defined narrowly in terms of what could be measured, tested, and repeated. Philosophical naturalism, the assumption that nature is a closed system of cause and effect, gradually became the default framework for interpreting the world. Although this shift began within philosophy and science, its influence did not remain confined there. Over time, these assumptions seeped into theology itself. Christians learned to affirm the authority of Scripture while subtly reinterpreting its supernatural claims into categories acceptable to a disenchanted age. Angels became metaphors. Demons became psychological conditions. Spiritual warfare became internal struggle. The language of Scripture remained, but its ontological weight was quietly reduced.²¹

The cost of this translation has been significant. In seeking intellectual respectability, Christianity has often surrendered internal coherence. The biblical authors were not embarrassed by an enchanted cosmos. They did not feel compelled to defend the existence of spiritual beings, divine councils, or cosmic conflict. They proclaimed God’s truth within a world they understood to be populated by both visible and invisible agents under God’s sovereign rule. Scripture consistently assumes that reality includes more than what human senses can access and more than what material explanation alone can account for. Recovering this worldview does not require rejecting science or reason, both of which Scripture affirms as gifts of God. It requires recognizing that science addresses material processes, while Scripture addresses ultimate agency, purpose, and meaning. When modern naturalism is allowed to dictate what Scripture is permitted to say, the Bible is forced into categories it never shared. Allowing Scripture to speak on its own terms restores not only its supernatural vision, but also the theological coherence that vision provides.²²

A Common Objection: “Isn’t This Just Ancient Mythology?”

At this point, some readers will object that what has been described sounds less like theology and more like ancient mythology. an outdated cosmology shared by pre-scientific cultures and later corrected by modern knowledge. But this objection misunderstands both the nature of Scripture and the claim being made. The biblical authors were not offering speculative explanations for natural phenomena, nor were they confusing spiritual reality with physical mechanics. They were describing a metaphysical framework in which God and created spiritual beings exist and act, a framework that does not compete with scientific explanations of how the natural world functions. Science investigates material causes; Scripture addresses ultimate agency, meaning, and purpose. Rejecting the Bible’s supernatural worldview is therefore not an advance in knowledge but a philosophical decision to restrict reality to what can be measured. That decision is not demanded by science itself, it is imported from modern naturalism. The question, then, is not whether ancient people believed in spirits, but whether modern readers are justified in assuming that reality is closed to the very dimensions Scripture consistently affirms.

Reclaiming the Supernatural Worldview of Scripture

Taken together, the themes explored in this blog reveal a consistent and deeply integrated supernatural worldview running through Scripture. From the disciples’ fear of spirits, to the unseen armies surrounding Elisha, to the divine council, cosmic powers over nations, angelic rebellion, conscious dead, and the cosmic scope of redemption, the Bible assumes a reality far richer than modern Christianity often allows. These elements are not fringe or optional. They form the background against which the gospel itself makes sense.

To reclaim the supernatural worldview of Scripture is not to become credulous or anti-intellectual. It is to read the Bible honestly, on its own terms, rather than filtering it through modern assumptions it never shared. When we recover this worldview, Scripture becomes more coherent, Christ’s work becomes more glorious, and the gospel regains its cosmic depth. The call before the church is not to tame the Bible for modern comfort, but to let the Bible reshape our vision of reality. Only then can we truly say that we believe the world Scripture describes—and the God who reigns over it.

Footnotes

- N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992).

- Craig S. Keener, Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011).

- John Walton, The Lost World of the Old Testament (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2009).

- Tremper Longman III, Job (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012).

- Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2015).

- Gerald H. Wilson, Psalms Volume 2 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002).

- Daniel I. Block, Deuteronomy (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012).

- Clinton E. Arnold, Powers of Darkness (Downers Grove: IVP, 1992).

- Loren T. Stuckenbruck, The Myth of Rebellious Angels (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014).

- Richard Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2017).

- John Goldingay, Ezekiel (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016).

- Peter Schäfer, The Origins of Jewish Mysticism (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009).

- Bruce K. Waltke, An Old Testament Theology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007).

- Meredith G. Kline, Images of the Spirit (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1980).

- Gordon J. Wenham, Numbers (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 1981).

- Douglas J. Moo, Galatians (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013).

- Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997).

- G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999).

- N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003).

- Greg Boyd, God at War (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 1997).

- Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

- Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Leave a comment